Robert Brunner: Taking Design from Good to Great

About

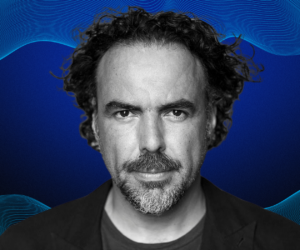

Today’s guest is Robert Brunner, founder and creative director of Ammunition. Robert is one of the world’s foremost industrial designers, having worked on popular products from the iconic Beats headphones to the omnipresent Square terminal to the Barnes & Noble Nook e-reader. In this episode, Robert shares his insights about the role that design plays in connecting people to brands and how he helps companies tell stories through their products.

Transcript

Charlie Melcher:

I’m Charlie Melcher, founder and CEO of the Future of Storytelling. Hello and welcome to the FoST Podcast.

Before we get started, I wanted to share some exciting news. I’ve been invited to speak at this year’s South by Southwest Conference on March 10th. My talk is entitled, Living Stories: How Immersive Experiences Are Reinventing Media, Disrupting Marketing, and Transforming Audiences, and I’ll be making a special announcement there as well. If you’re going to be at South By Southwest in Austin, please come by to join me for the session and for more information, please see the details in this episode’s description.

Today I’m speaking with Robert Brunner, founder and creative director of Ammunition and lead designer for Beats by Dr. Dre. Robert is one of the world’s foremost industrial designers. If you don’t recognize him by name, you’ll almost certainly recognize one of the products that he’s worked on— from the iconic Beats headphones to the omnipresent Square terminal, to the Barnes and Noble Nook e-reader, to name just a few. Before starting his own studio, Robert was a director of industrial design at Apple, where he oversaw design direction for all of their product lines and founded their pioneering internal design department. His work is in the permanent collections of the New York and San Francisco Museums of Modern Art, and he’s been named one of Fast Company’s “most creative people in business.” Robert’s very skilled and insightful about the role that design plays in connecting people to brands, and in this way he helps companies tell stories through their products. Please join me in welcoming Robert Brunner to the FoST podcast.

Robert, welcome to the Future Storytelling Podcast.

Robert Brunner:

Thank you, Charlie. It’s great to be here.

Charlie Melcher:

So I have been a huge fan of your work for many, many years and didn’t realize it was your work, which is crazy, but perhaps part of how things work when you are the person or lead the team that designs things that people use every day in their lives.

Robert Brunner:

Yeah, it’s funny you say that. I’m actually in the process of writing my second book and my co-author was explaining to our publisher: “yeah, Robert is the most influential designer you’ve never heard of.” And for a minute I was insulted, and then I realized, well, that’s probably a compliment, so that’s all right.

Charlie Melcher:

Well, I think so. I mean, when you do your job, people have this tremendous love for the things that you’ve made, but often they’re so seamless, they’re so well designed that people don’t even think about that. They just take it for granted. Do you feel sometimes that your craft is taken for granted?

Robert Brunner:

That’s a good question because a lot of times I think people only comment on or notice design when it’s bad, right? That thing, a thing broke, didn’t work, and that’s when you say, “Who’s the son of a bitch who designed this thing?” That said, though, I think in the last decade, the understanding and appreciation for industrial design has grown, of course driven a lot by Apple and the contributions that they’ve made to design. But I think in general, I find that people are, when I tell them what they do, I’m like, oh, yeah. Yeah. That’s fantastic.

Charlie Melcher:

You spent a bunch of years at Apple, right? That’s one of the sort of formative stops along your personal journey. What was that like?

Robert Brunner:

Well, it was amazing. It was really challenging. I had started working with Apple. I had a consultancy called Lunar at the time with a couple guys, and Apple became one of our clients. And it was interesting. Originally we were the way Apple was, we weren’t supposed to tell anybody. We were working for Apple, which was kind of like, how do you hold that inside when you’re like a 27-year-old designer? But yeah, and then through a process I was recruited and asked to become their director of industrial design. I look back and it was like, I think I was like 29 or 30. I look back now, I think that’s pretty crazy. Here’s a guy with no corporate design experience taking over this program, figuring out how things really get done, figuring out the risks that people take personally take to try and make something happen and go out in the world. And that actually was one of the things that really stuck with me as I went back to consulting of really having this sort of care and responsibility of working with people and helping them bring something to market and realizing more so than me, their jobs are on the line. And all that was just an incredible learning experience.

Charlie Melcher:

So that seems to be very relevant to what you do today with your own firm because you’re there every day with entrepreneurs whose life depends on how this product does that they’ve come to you for help with.

Robert Brunner:

When I first started ammunition, after I left Apple, I went to Pentagram, and then after about 10 years, I said, okay, I’m going to start something new that’s more product focused. And one of the reasons I did, I had this epiphany about what we did and the value of it in that I was happy to just get a good project. And so you get a good project, it’s really cool to work on, you get a great portfolio piece, you make enough money to pay your people and pay yourself, and then you watch it go out in the world and create hundreds of millions of dollars of value. And I realized I wasn’t thinking of my work as intellectual property. I was just thinking of as service. And I had friends who had write some lines of code and retire.

But the interesting thing about it is, while originally it was driven economically, what I started to realize is it created a very different working relationship when you were invested with these guys in that I was taken more seriously because I was putting my money on the line. But then also I took the work more seriously. Not that I didn’t take it seriously, but I really began to view it as what can I do to make this enterprise successful? And so we began to develop this approach where we were working with, even though we were clients, working with companies like we were in the company and we had a responsibility to their success, and that just created a different style of working. How does that affect your creative process? My creative process, much, the chagrin of my team is to be very thorough. We do our research, then I say, go shove that in a drawer and look at everything from a 360 degree point of view, and every possibility, every permutation, everything that we do just sort of look at what are the opportunities that we can uncover here before we start trying to apply constraints on it.

That combined with this idea of, look, we’re here to, we’re here to do great work. We’re here to create art, we’re here to drive culture, but first and foremost, we’re here to help this group of people create something meaningful and valuable in the world. And so it’s really focused around using all that energy, attention about uncovering these opportunities and then figuring out how to deliver them.

Charlie Melcher:

The story around beats and the work you did with Dre and the team and that very seminal design, can you tell us the story of that project?

Robert Brunner:

Well, I just had a realization when LinkedIn sends you reminders and that I’ve been effectively working on beats and I continue to for 20 years, which is kind of mind boggling to think about how it started. I was originally approached by a third party, and he had this idea to combine musical talent with products and put that together from a design and marketing point of view. And through him, I was introduced to Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine, and we’d have meetings with Will.i.am and Pharrell and whoever happened to be in the building at the time, and I’m a design nerd. But we clicked and later on I realized what it was that I was reading an interview that Jimmy had given for Rolling Stone. He talked about how he worked with artists and how he would push them, and I realized that’s exactly the way he treated me, right?

I’d get these calls from him on Saturday mornings and say, “Robert, what the hell?” Just screaming at me. But it was kind of this thing where that’s just how he pushed people, and he viewed me as an artist. And Dre, he said, people aren’t hearing my music. I said, well, what do you mean by that? He said, well, I spent all my time making music, and then people go out and listen to it on those crappy white earbuds. I was this quote, which I always thought was funny, that crappy white earbud company eventually bought them. And so that was really a lot of impetus. The impetus around the product was to build from an acoustic point of view, a headphone that was really tuned and tweaked for hip hop and rock music. For me, headphones was some of the more challenging things to design. When I dove into it and started looking at headphones, I was going to realize that they were not designed on the body.

No one had really sort of designed them on the head, thought of them as wearable technology, and really made something that people would not just perform but would make them feel good and printed out a picture of a typical headphone. I drew this single line from ear to ear on it and said, wouldn’t it be great if I could take all this and clean it up and just make something beautiful and elegant that sat well on the body, and that was really the impetus for that first design, and it’s really been the same approach we’ve carried on for this entire 20 years.

Charlie Melcher:

You mentioned the idea of making it feel good, that good design sort of feels good for the user. Can you elaborate on that? How do you mean that?

Robert Brunner:

Well, I mean, it’s actually a dominant part of our work, and it’s sort of the emotional currency of physical things. One of the reasons I got into industrial design when I finally figured out what it was and was interested is that people have an interesting relationship with things of objects. In many ways, people will define themselves by the things they acquire and surround themselves with, whether that’s the furniture in your home, the shoes that you wear, the car that you drive, the glasses that you have on all these things you choose as an expression of who you are. And that was a big thing about the headphones. We thought what we wanted to achieve is when that kid walks out of his little studio apartment and puts those headphones on his head, or even just around his neck, he’s transformed, right? He’s got this connection, to Dre and other artists and athletes that feels empowering and feels positive. And when you start to think about the products that you keep in your life, many times it’s about what you feel and then how they’ve made you feel. And so that’s the thing that great industrial design, and it’s connected to a brand experience, what it can do is really sort of shrink that gap between the user and the company. And that connection is almost always emotional.

Charlie Melcher:

As we at the future of storytelling are very focused on storytelling and different kinds of stories, and so many of the traditional forms of storytelling just appeal to the eyes and the ears. You sit and you watch, or you listen. I think there’s a lot to learn from one of the world’s great industrial designers as yourself, because you’re also telling stories to the body. You are designing for how something feels, and a lot of that is even subconscious, I would imagine, right? Often we’re not conscious of how something fits correctly in our hand or feels right on the body, but you are, when you talk about obsessing about every detail or the finish, the feel, the fit, you’re really talking about how do you speak to the body so that it instinctively feels right for somebody when they pick it up or put it on or use it. Any insights in talking to the body?

Robert Brunner:

Well, I mean, I think I really like the description of what we do as storytelling because it is, and there’s different ways of telling stories and different ways of communicating with people, and one of the things that I think always makes a great product is when it invites you in, when you get something, and yes, you want to take it out of the box and start using it, but then it starts drawing you in to learn about it. It starts surprising you with what it can do. Then there’s this whole journey that occurs that’s an unfolding of what something is, but it is very much a story in that sense. For me, I really enjoy, we work with a lot of founders of startups and sort of really understanding them and their passions and their purpose and the things that they do to actually bring the amazing things out into the world, and that I find to be a really fascinating thing, in that many times the leaders of the company will have this: “if we build it, they will come” sort of feeling right? They have this amazing idea, and all we got to do is get it out into the world. Almost never true. And so we often try to work with them. We have this story that we’ve created, and when it launches, that’s just the beginning of the story. You have to continue to go out and build on that story and bring it into people’s lives and contextualize it for them and continue to grow that energy and impetus that your launch created. We’ve often thought about, well, maybe we should have a stronger sort of marketing component of what we do, because really if you spend all this time sort of fussing around and figuring out what this story is, maybe we should help people learn how to tell it better, because that’s ultimately many times what makes something compelling.

Charlie Melcher:

What percentage do you think of the success of a product is its design versus its marketing or other elements?

Robert Brunner:

Well, of course that’s variable, and there’ll be times when you see something that’s a bad piece of design that’s successful, and that’s an occurrence. That’s not uncommon. But when I look at the things that really have made significant change that really have created something, whether it’s created a new market, created a new capability, created some movement and culture, there’s always design behind it. Design is really the interface playing between you and the outside world, you the company, and the outside world, and so everything you put out there should be done the best possible way. That’s really, really defining who you are. Technology enables, right? Technology can allow amazing things to happen, but it’s designed that establishes it in people’s lives because it doesn’t matter how amazing it is or what it can do if nobody gets it, nobody understands it or nobody desires it, and those are the things that design gives you.

Charlie Melcher:

I don’t know why, but I often think about the hero’s journey in that conceit, that structure. There’s this idea that every hero has a mentor, and along the way the mentor provides some sort of magical object. Think of the lightsaber from Obi-wan Kenobi to Luke Skywalker. Hearing you describe the way a pair of headphones can feel like a superpower, it makes me think that you are the one who’s kind of designing the special object, the magical object that’s going to empower the user on their journey of life to be successful and become the hero, and that when you do it correctly, they have a similar kind of emotional connection because it’s actually transforming their lives. It’s enabling them to do something differently or be someone differently in a different way.

Robert Brunner:

Yeah. Yeah. It’s a really interesting thing, and it’s something you can never discount the human condition. Early on in my career, I had this project designing this DNA sequencer. It was a piece of laboratory analysis equipment, probably one of the most functionally driven projects I’d ever done, and so as usually went out and interviewed some lab leads to just see what they’re looking for, and all they talked about was in a competitive context, so they wanted to be the first to discover this thing or the first to have the most amazing equipments that’s going to allow them to reach this point, and almost everything was in this very emotional context, and I remember that just striking me that it’s always there. No matter what you’re doing, there is always an emotional piece to it, and it’s never something to be discounted and when you can, it’s something to be understood and leveraged.

Charlie Melcher:

When you go about designing a product, you’re thinking about the whole user journey. You’re thinking from marketing to box opening to use, and end of life. Talk a little bit about how you think about the whole journey of the life of a product.

Robert Brunner:

I mean, I spend the vast majority of my time in the world of objects obsessing about them, fussing over them, getting every detail, the materials just right, everything, trying to work it through mass production to deliver it, but ultimately great products. There’s a level above that, that’s around the idea. You’re using every opportunity you can to create a relationship with people, so you need to figure out what that is. And the first book I wrote, we coined this term called the experience supply chain, in that there’s this whole army of people that are delivering something, and all along the way, it’s about delivering this experience and how it shows up and how everyone understands and embodies that experience in their particular part of the puzzle. That’s the thing that’s coming out in the world.

Charlie Melcher:

You’ve talked about the difference between good design and great design before. What is that difference for you?

Robert Brunner:

You could define good design a lot of ways, but ultimately it does the job well, useful, usable, desirable, attractive, functional. It’s competitive, manufacturable, I can attain it, and the stuff that you need to do that you have to understand the opportunity, have the talents, tools, process, experience, all those things to get you to create a good piece of design, and what I started to look at was this idea of great. What I realized is probably, I don’t know what percentage of our work—under 10% falls into this category of “great,” in which that I best describe it as it moves the needle, right? It’s inspiring, it’s empowering, it’s transformative. It challenges norms, culturally relevant. I mentioned this portal to something bigger. It’s socially positive. It creates high value, and when you start diving deeper, the tool set to get there is very different.

You have to have this view of the world that’s broader and supportive of risks, all the cultural intelligence, all these things that take you to these things that are great, that actually change things, right? And what I began to realize, there’s this special form of leadership that’s involved in making something great, this sort of idea of non-negotiable purpose and clarity and focus and tenacity and commitment to craft and all these things. It’s not necessarily the exclusive territory of actors, elite athletes and billionaire serial entrepreneurs. It’s actually things that people can’t embody when they do their work. It’s just an understanding that there is this sort of different level of commitment of going from good to great, and the counterside of that, which is something that’s become very pervasive in our society, is the acceptance of mediocrity. Fine is fine, right? Good enough is good enough. I’m not going to take a risk, and in product development, there’s a lot of simplification, all these things. Yeah, of course it makes total sense, but when you end up throwing innovation out the window and you end up not making something really great, so what I began to realize is the leaders that do that run counter that and take a very different approach. A lot of things that don’t happen often, there’s complexity and nuance, but I do believe it’s something that people can gravitate and aspire to in their work.

Charlie Melcher:

That resonates really powerfully for me, Robert. I ask this same question of myself and my company. We make a lot of things, and we’re known for making beautiful books, but sometimes our books are just really good, and on occasion they really transcend that and become great. There’s so many forces and pressures, such inertia to just get it out, do it in the way that it’s economical, safe, timely. There’s so many factors that go into not taking risks or not pushing beyond the envelope or not trying to do something out of the ordinary. It’s very hard to push against all of those.

Robert Brunner:

Yeah, no, it is, and I said that this whole notion of mediocrity, and it doesn’t just live in individuals, it breeds in communities, but the truth is it’s a lie, right? It tells you that safety is better than effort. That good enough is a badge of honor. That avoiding failure is the same as succeeding, but it’s not. I mean, the reality is it costs you more than any failure ever could by sense of a missed opportunity. So the idea of great design is something that can be achieved and can be achieved with regularity. It just takes a certain commitment and tenacity and understanding to do it.

Charlie Melcher:

You said before that you really like the term storytelling and referring to industrial design or the work that you do, and storytelling tends to have a kind of language about it. Again, depending on the medium. How do you describe the language, the storytelling language of industrial design?

Robert Brunner:

I mean, I’ll go back to really early in my career, I think I was actually in school and I went to see a lecture by the designer and architect, Mario Bellini. He was just sitting on the stage in a talking and behind him there were two slide projectors running simultaneously with these objects that he would show. So I remember one was a side profile of a six series BMW, and then a side profile of a great white shark. This knob on one of his typewriters, and then a closeup on a woman’s breast—creating these sort of abstract but emotional connections of imagery that I remember just sitting there and saying, that’s incredible, but that’s it. That’s right. There’s this language there that you use to connect with people or invoke emotion. The language of industrial design is imagery oriented, it’s tactile, very gut level kind of communication that occurs with a product. Yes, of course, there’s a lot of very direct stuff, and when you get into interaction design and functionality and how things work, but ultimately there’s this language that’s connecting with you at this very sensory level in terms of your eyes, your hands, what you feel, what you hear—all these things, and it is something that takes a long time to figure out and master honestly.

Charlie Melcher:

How do you think i’s going to change when AI becomes a bigger part of the tool set and a more adopted or adapted collaborator for doing industrial design?

Robert Brunner:

There’s always these waves of technology that come through design, and so I started out on a drafting machine with an HP calculator, and so much of my job was about math really, because I’d had this idea on something and then have to figure out, okay, how am I going to describe this to somebody else? 2D CAD came along and all of a sudden liberated me from that math, right? I didn’t need to do as much math to lay something out and get all the numerically defined, and it keeps going, right? To 3D, printing, advanced visualization. There’s always these moments and what the technology always does, it creates space for something else, something better. All of a sudden, I have more time to think about something else than doing trigonometry, and that’s kind of what’s happening now with AI, that there’s just moving to higher levels of automation.

My job and our jobs as designers is kind of moving towards this idea of producer, director, editor, right? In that, as the tools like Midjourney and others that get more capable of developing concepts based on prompts and information, being able to have these tools that generate things, but you still need to be… you need to produce, figure out what it is. You need to direct it. You need to edit it. So I think that’s a little bit what’s happening with the profession.

I’m very much, as you’ve probably figured out, a believer between this connection between people and things, and part of that connection is because people ultimately want to connect with other people, and many times through design you do that. You connect with the designer, you know that there’s someone that’s authored this, someone that’s created this. For me, I’m a bit of an optimist and that I think, I don’t think, and I could be proven wrong, that artificial intelligence will be able to replicate that level of experience that people bring to designing things, but we’ll see. We’ll see, it could be wrong.

Charlie Melcher:

I certainly agree with you that people want connection with other people and that even if they’re not conscious of it, that there is some humanity in all of the objects that you design. I started the conversation by saying you were sort of like the anonymous, best kept secret, but in fact, I think you’re absolutely right that you’re not at all anonymous, that people are drawn to the beautiful things you and your team designed because specifically of you. They just haven’t had the pleasure of sitting down with you the way I have so…

Robert Brunner:

Well, it’s a fun job, and that’s kept me going for so long. It never gets old because it’s always, always changing, but it’s also a privilege, right? You get to go into your work every day and create something that’s going to affect people’s lives, hopefully in a positive way, and every couple months there’s another opportunity to do that. So I view it as a privilege to do it.

Charlie Melcher:

Robert, thank you so much for sharing your journey and experience and work and just honored to get to spend time with you, so thank you.

Robert Brunner:

Well, thank you very much. I’ve enjoyed it a lot. Thank you.

Charlie Melcher:

This has been the Future of Storytelling podcast. Thanks for listening. We’re honored and proud to have so many thoughtful storytellers who are driving culture as part of our FoST family. To learn more and stay connected, check out our website at fost.org. There you can listen to more episodes of this show and subscribe to our free monthly newsletter FoST in Thought, I hope you’ll join our community.

The FoST Podcast is produced by Melcher Media in collaboration with our talented production partners, Charts & Leisure. I hope to see you again soon for another deep dive into the world of storytelling. Until then, please be safe, stay strong, and story on.