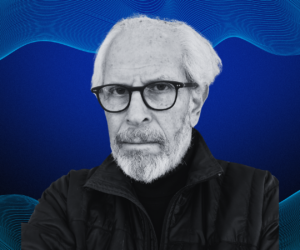

Jeffrey Seller: Memoirs of a Theater Kid

About

Jeffrey Seller is the legendary Broadway producer behind shows like Rent, Hamilton, In the Heights, and more. His shows have won a combined 22 Tony Awards, including four for Best Musical, and he’s the only producer to have mounted two shows that went on to win the Pulitzer Prize. This spring, Jeffrey published his autobiography, Theater Kid, an honest and moving reflection on his path to finding his place on Broadway, as well as an invaluable source of wisdom for anyone interested in building a business in a creative field. In this episode, he shares openly about his journey to finding himself in theater, stories of his creative collaboration with artistic powerhouses like Jonathan Larson and Lin-Manuel Miranda, his philosophy of good producing, and more.

Additional Links

Transcript

Charlie Melcher:

Hi, I’m Charlie Melcher. Welcome to the Future of Storytelling podcast. Today I’m excited to be welcoming an old friend onto the show: celebrated Broadway producer Jeffrey Seller. I first met Jeffrey almost 30 years ago when he hired me and my team at Melcher Media to create a companion book for the hit Broadway musical Rent. I’ve since watched as his remarkable instincts and talents have led him to become one of the most successful American producers of all time, having brought us groundbreaking musicals like Rent, Avenue Q, In the Heights, and Hamilton. His shows have won a combined 22 Tony Awards, including four for Best Musical, and he’s the only producer to have mounted two shows, Hamilton and Rent, that won the Pulitzer Prize. Jeffrey’s Broadway productions and tours have grossed over $4.6 billion and reached more than 43 million attendees—including many who could not have otherwise afforded it without the revolutionary $20 ticket lottery that he pioneered for rent. This past May, Jeffrey released his autobiography Theater Kid, published by Simon and Schuster. It’s a moving and invaluable read for anyone interested in theater, artistic collaboration, or building a business in a creative field. Please join me in extending a warm welcome to my friend Jeffrey Seller.

Jeffrey, welcome to the Future Storytelling Podcast.

Jeffery Seller:

Hi, Charlie. I’m so happy to be here with you after all those years admiring and enjoying and participating in the Future of Storytelling.

Charlie Melcher:

Thank you. I so enjoyed reading your book. I was blown away by it, to be honest, and I couldn’t believe just how intimate, how honest, even at times revealing—and all of that, and humble, which also blew me away because a person of your success and stature—most wouldn’t be quite as humble as you were in the book. So anyway, I wanted to start by congratulating you on it and asking what was it that made you decide to write a book that was so revealing at this point in your life?

Jeffery Seller:

This is going to sound heavy, but I’m an atheist. And I am also a man who’s now 60, wrote the book somewhere between 54 and 59, and I needed to write this book to answer the question, where am I? How did I get here? And what am I doing here? So this book was actually my own exercise in answering my own existential questions. For me, that question was how does this kid from little Oak Park, Michigan from a neighborhood the kids called Cardboard Village, who was adopted, poor, gay, and Jewish—

Charlie Melcher:

You had everything going for you.

Jeffery Seller:

Yeah. How does this outsider, or at least this kid who feels like an outsider get from Oak Park, Michigan to Rent on Broadway and Hamilton on Broadway? My story’s unlikely and I needed to untangle it.

Charlie Melcher:

Well, there’s no question that in the honest discovery or revealing of your own personal story, we can see these threads throughout that pull through to help understand how you got to where you are today. What turned out to be some of those key moments that you think were most influential in making you this pillar of your industry today?

Jeffery Seller:

I realized that there are these two extraordinary forces with me, or I’m going to say three. One is being adopted. We adoptees are different. We start from a very different place. That was a big fueling moment for me. And then the simultaneous discovery of theater, which of course became my way out, but it also became my way of enjoying my life in a very unique way because it became the most enjoyable part of my life. And then we have a bunch of moments. The first being that my father had this devastating motorcycle accident when I was two weeks before my fifth birthday, which changed him forever after he crashed onto I-94 in the state of Michigan head first on a motorcycle and suffered terrible brain damage. The man who came back was not the man who went away. And so you have that as a pivotal moment, and then you have being in that first play in school as a pivotal moment, right? There’s so many.

Charlie Melcher:

Yep. Or producing, directing a play at summer camp. I thought that was a great story. I love that story.

Jeffery Seller:

Yeah. Directing Aesop’s Fables for a bunch of 14 year olds, two of which I recently had contact with for the first time—

Charlie Melcher:

Since then.

Jeffery Seller:

Since they were in it. There were—

Charlie Melcher:

Which two?

Jeffery Seller:

The Stein twins.

Charlie Melcher:

The Stein twins? Oh no, they’re like the stars of the show!

Jeffery Seller:

The stars of the show, who—I was so proud of myself because I thought, oh, if I cast these identical twins in the same role, then I can play with the audience and fool the audience because they can show up in places they should not be showing up in. And they were the stars of the play, stars of the summer, and after that summer, when they were 14 and I was 18, I never saw or heard from them again. And through this book, they came back.

Charlie Melcher:

They came out.

Jeffery Seller:

And now they’re 55-year-old women. And one of them found out about the book because her friend said, “do you know you’re in a book?” And she didn’t know she was in a book.

Charlie Melcher:

She didn’t know you had gone on to—

Jeffery Seller:

She had no idea that her camp counselor, Jeffrey Seller, became the producer of Rent or Hamilton or any of those shows.

Charlie Melcher:

And then you moved to New York, and—again, I just love the stories of you starting out professionally and having to work your way up from the bottom like everybody else, having to get paid poorly as everyone does in theater and in most creative professions, honestly. A lot of parallels between that and starting out in publishing. And just sort of working your way up. And I guess one of the things that really came to my mind was how you had to learn the fundamentals of the business.

Jeffery Seller:

Yes. And how valuable that was as preparation. It was kind of like getting a graduate degree without having to go to graduate school. When I was 22, I got my first job in commercial theater at Barry and Fran Weissler’s office. Barry and Fran in the eighties were the purveyors of these big revivals of well-known musicals, and they would have big stars in them. And they were also executive producing a musical that I was heavily involved in booking, which was Robert Goulet in South Pacific. Now, when I got to that office, I thought: “Robert Goulet in South Pacific? That is so cheesy. Why would anyone want to go see that?” Because I was the kid who loved Dreamgirls and loved A Chorus Line and loved Evita, and the contemporary musicals of our day. I’m like, who wants to go backwards? But I got a job as the assistant to the booking head, and we had to book these shows all over America from Richmond, Virginia to Denver, Colorado to Sacramento, California, and every city in between. And what I learned from that, first of all, was there were a lot of people that wanted to see Robert Goulet in South Pacific. There really was an audience for these classic musicals with these older stars.

So one is I learned a lot about what America likes, but then I learned the art of negotiation and I learned how to handle pressure. The pressure on the booker is so heavy that you have to book every single week consecutively, and you can’t go from Richmond to Denver because it’s too far away. So if you close on Sunday night in Richmond, you have to go somewhere not too far away like Louisville, Kentucky. So you have to coordinate, you have to negotiate, and you have to sell. And I learned all of those things by working at Fran and Barry’s office.

Charlie Melcher:

And you also share with us in the book some of those learnings. I felt like I was starting to learn the fundamentals of the business and some of the terms, and—I just felt like it was so revealing in how you create a successful producer. Right? That you had both a training in the creative side in directing and taking the classes and working with talent. I just kept thinking: all of these things wove into making you be ready for when the moment came.

Jeffery Seller:

Yeah. What was so amazing was being able to learn the nuts and bolts of the business. And keep in mind: touring at that time was a bigger business than even Broadway. So if you are interested in what we call “Broadway theater,” Broadway and the road are completely symbiotic. One cannot exist without the other. So learning the nuts and bolts of the road was like getting the best base for my own education. And what was amazing is it was while I was working by day at the Weissler’s, that’s when I was going off with my friends and making a new musical to do The Temple on West 83rd Street. So I am continuing to develop relationships with young composers and lyricists and book writers. And of course that’s when I met Jonathan Larson, who changed my life and ultimately changed millions of lives.

Charlie Melcher:

So how did you spot that talent? Jonathan Larson had been struggling for years, waiting tables with those dirty sneakers and trying to write the great contemporary musical. How did you figure out that he was the one?

Jeffery Seller:

So in the fall of ’90, I was working at the Weissler’s still, and by that point I’d been working there for over three years, three and a half years. And I was no longer happy in my job. I was no longer fulfilled by my job, and I yearned deeply to actually be a producer, but I knew I couldn’t afford to be a producer yet. It was right then that my friend Beth said to me, “Hey, I’m going to see this rock monologue tonight. You want to go?” And I looked at the flyer and it said, “Boho Days: a rock monologue by Jonathan Larson.” And I thought, “what’s a rock monologue?” That’s really cool, but I’d never heard of that before. And we get to this small performance space and there’s a brick wall in the back and a piano. And then out comes this tall lanky guy with curly hair and big ears.

His name is Jonathan. And he attacks the piano. And he’s ferociously playing these songs. And what is this show about? He turning 30 and he is a 30-year-old composer of rock musicals that no one wants to produce. And he lives in the fourth floor walkup of this ramshackle apartment on Greenwich Street with roommates. And there’s really a bathtub in the kitchen, and they have to switch off on who gets to go in the kitchen and take a shower in the morning. And he works at the Moondance Diner as a waiter, and his friend offers him a job at an advertising agency writing copy, where if he takes this job, he’ll finally make real money. He can get a real apartment, he can get health insurance and start living an adult life. The question of the musical is: do I keep writing rock musicals that nobody wants to produce or do I finally take this job and sell out? So the day after the show, I wrote him a letter saying, “I want to produce your musicals.”

And then just to bring it back to the Weissler office… About two weeks later, it’s now the day after my 26th birthday because the day before they’d given me that cake they give in offices where everybody comes in and sings “Happy Birthday.” I guess they waited until the next day because the day after they gave me that cake, I am sitting in the conference room, where they sang, happy birthday, and I’m eating my carrots and celery and peanut butter and jelly sandwich. And in walks my boss, she has that envelope and she says, “We have to talk. You don’t want to be here. You don’t want to be a booker. You want to be a producer. You should go off and do what you need to do.” And I said, “so I guess Friday is my last day?” She went, “no, you can leave now.” And as she was saying that the all intercom goes off—you know, when they can’t find you because I’m not in my office—

Charlie Melcher:

What are the chances of this? This sounds like fiction.

Jeffery Seller:

I know, but it’s true. So God help me. And the receptionist says, “Jeffrey, Jonathan Larson on line six.” And I had to say, “take a message” because I was so busy getting fired! So when I went home, I called him back and I said, “Jonathan, this is Jeffrey Seller.” And he said, “how are you?” And I went, “I don’t know. I was just fired.” He said, “is that a good thing or a bad thing?” And I said, “well, if I am to believe anything I heard in your musical last night, it has to be a good thing.”

Charlie Melcher:

Unbelievable story. And then came Rent.

Jeffery Seller:

Yeah. So that’s the fall of ’90, and that is the beginning of our partnership, professional relationship, friendship that culminates five and a half years later with Rent.

Charlie Melcher:

Another thing that gave me chills in the book, and we talked about this idea of there being these sort of loops or threads—Tell us about watching the nightly news and seeing the producer David Merrick make an announcement on opening night of 42nd Street.

Jeffery Seller:

Yeah, there’s such a thread between that moment that I witnessed with my parents and what happened with Rent all those years later. So when I am in 10th grade, the summer between sophomore and junior year, I’m working at this awful Katz’s Deli, and, you know, I’m making the three bucks an hour and maybe an extra buck for the tips at the end of the night. I come home at 10:30, and then I would watch the nightly news with my mom and dad. And I’m watching the Channel Seven Eyewitness News when Diana Lewis says, we have a big story that just came in from New York, which was that night was the opening night of the big new musical 42nd Street, directed and choreographed by the Gower Champion and produced by the great David Merrick. And at the end of the triumphant opening night performance, producer David Merrick takes the stage and the audience is cheering and screaming and throwing flowers to the cast.

And David Merrick says, “no, no, I have something terrible to tell you.” And the audience then cheers even louder because—

Charlie Melcher:

They laugh, yeah.

Jeffery Seller:

They think he’s being sarcastic. And he said, “no, stop. Gower Champion died today.” The legendary director-choreographer. And the cast starts screaming behind him. And then you see the great actor Jerry Orbach scream up, “Bring in the curtain!” and then the curtain falls. And that story becomes news all over America. And I was awestruck by the theater of that moment, by the drama, by the surprise. So this producer held back the news that Gower Champion died until after the end of the opening night performance. He also called in all of the press—ABC, NBC, CBS—and they were all there taping that moment. And what he did with that moment is he instantly made 42nd Street a show everybody in America knew about on its opening night. And that was an extraordinary event for the theater. He took a musical and he got it off of the arts page and onto the news page.

Charlie Melcher:

Okay. So I understand that your young mind is analyzing the strategy there, but now tell us the story of opening of Rent and—was it similarly a strategy?

Jeffery Seller:

God no. It couldn’t be. But what you are alluding to, which some listeners will know and some will not, is that tragically, two hours after the final dress rehearsal of Rent on January 25th of 1996, Jonathan at age 35 died of an aortic aneurysm—a tear in his aorta, in his heart—in his apartment on Greenwich Street. He had been suffering from symptoms of flu, nausea, chest pain over the previous week. And he soldiered on. And we had a raucous and effective dress rehearsal before an audience of family and friends. I was able to tell him that night that he did it. He finally got the show to where it needed to be. And he felt some sense of satisfaction. But he was also eager to go home and think about what he wanted to implement the next day. And he did one more activity before he went home, which was, he had his first ever interview with a reporter from The New York Times.

They were going to do a story about the 100th anniversary of La Bohème and this new La Bohème update called Rent. So the last time I saw him, he was sitting in the box office, which was the only quiet place that he and the reporter and music critic Anthony Tommasini could go to. And that was the last time I saw Jonathan, because he went home and died. And I will say that when I was informed the next morning that Jonathan had died, I was shocked, I was sad, I was paralyzed. And I also immediately thought of Gower Champion, and I said to myself, “Jonathan’s going to become a legend.”

Charlie Melcher:

And he is. And a lot of that had to do with your contribution and many others, but yours definitely.

Jeffery Seller:

Well, we got the show on.

Charlie Melcher:

Yeah. Boy did you.

Jeffery Seller:

We got the show on. And I say that with incredible mixed feelings because the next night we were supposed to have the first public paid performance, but Jim Nicola, the artistic director of New York Theater Workshop, wisely said, “You know what? We shouldn’t do that.” It’s too dangerous for the company to try to do this complicated show under this—Everyone was traumatized. So he said, let’s just read the show out loud, like meaning sing and read, sitting down at the tables. 150 people who were saddened, shocked, walked into that theater that night. And we all sat and the cast came out. They sat at those metal tables we all know about now, and sang and read the show. And with every number in Act 1, their commitment to the performance seemed to deepen. I mean, the second song in the show is the character Roger singing “One Song Glory,””one song before I go”…How do we listen to that less than 24 hours after Jonathan has died?

It was almost as if he had written his own death into his show about his friends, about his hopes and dreams, about his struggles. And by the end of the first act, when the cast gets to the Life Cafe and does “La Vie Bohème,” Daphne Rubin-Vega gets up on that table and starts dancing. And then Wilson Heredia, who plays Angel, gets up and the entire cast just got up and started doing “La Vie Bohème.” It was a triumphant end to Act 1. And then my business partner, Kevin, and I met Al and Nan Larson, Jonathan’s parents, for the first time. What do you say to a parent who has lost their son less than 24 hours? So we shake hands, we greet them, and Al Larson said—we of course expressed our sympathy, and Al says, “Johnny talked about you guys all the time, and we just have one thing to say to you: get his show on.” And we did.

Charlie Melcher:

That show had unbelievable impact. In fact, is it still running? Is it still traveling around the world now?

Jeffery Seller:

You know what? I have to tell you that there’s always a production of Rent somewhere because of the licensing, but it ran 12 years on Broadway. But then we had tours going that only ended about—I think about—we did one more tour even after COVID, so I think it finally ended in the summer of like ’22. So between ’96 and ’22, which would be 26 years, I think it was traveling throughout America for about 16 of those years. So there were breaks, but it just never seemed to stop. And what is so incredible about Jonathan’s legacy is that he had this vision: “I want to make musicals for our people, for my friends, for my generation. I want musicals for my generation that are our stories, our characters, and our music.” When young, high school senior at Hunter, Lin-Manuel Miranda, goes to see Rent with his girlfriend as a high school senior. He sits in the balcony, he watches Rent, and he says, “oh, I can write a musical about my community, with the music from my community, about my family and friends.” And what does that become? In the Heights.

And what does In The Heights lead to? Hamilton. There is no Next to Normal or Dear Evan Hansen or In the Heights or Hamilton without Rent. And Jonathan carries all of these amazing shows and creators on his shoulders.

Charlie Melcher:

Well, it was an incredible honor to be asked to work with you on that book and to try to help tell that story. And one of the things I loved about the story that we, as it was told in the book, was it was a chorus of voices of the people who knew him and loved him and worked with him, and it became their voices telling his story. So anyway, thank you for letting us work on that book.

Jeffery Seller:

It’s an essential part of the history of Rent. A book I treasure.

Charlie Melcher:

I also think we should mention that you were an innovator in opening up tickets at a lower price so that it wasn’t just a high-end wealthy audience. Can you just describe a little bit your contribution there?

Jeffery Seller:

Yeah, sure. One of the questions that my then-partner, Kevin and I absolutely had to confront when we were thinking about bringing Rent from New York Theater Workshop down on East Fourth Street all the way up to Broadway was: Will the Broadway crowd want to see this show and will the downtown crowd want to go to Broadway? And then more important, will the crowd for which Jonathan wrote this musical be able to afford to come see Rent? And we knew we had to do something about that. We came up with this idea: we’re going to sell 34 seats for 20 bucks every day, and we’re going to put ’em in the first two rows. We’re going to do 20 bucks, cash only, two hours before the show. And if we put ’em in the first two rows, they’ll start this wave of enthusiasm that’ll go from row A and B all the way to the back of the balcony.

And by creating this notion that you have to come stand in line, we were making yet another marketing effort, which was creating the line in front of the theater, which is always an attraction for selling more tickets. A year later, the lines were so popular that kids were sleeping overnight on 41st Street, and we were like, “someone’s going to get hurt.” So then we made it a lottery at six o’clock every night, and we started that with Rent, and that became a tradition for almost every musical on Broadway. When Lin and I did Hamilton 10 years ago, he said, “well, we have to do it as a Hamilton,” so we cut the price from 20 to 10.

Charlie Melcher:

Nice.

Jeffery Seller:

And then when we did raise prices at Hamilton, we expanded the number of seats to over 50 that were $10.

Charlie Melcher:

One of the things I just have in my mind, because you were talking about the strategy, it made me think of the story you tell around Mike Pence and his participation when he came—

Jeffery Seller:

Okay, that one was strategic. The Mike Pence story is absolutely a reaction in real time to an obstacle, and a strategy that is both political and a marketing strategy. I get a phone call at four o’clock on a Friday that Vice President-Elect, Mike Pence wants to come see Hamilton that night. This is a man who has made it very clear that he does not believe in gay marriage. He believes being gay is a sickness. This is a man who has made it very clear that a woman’s body is not her own and that she does not have agency over her own body. And this is a man who wants that company of Hamilton, of women and gay men and people of color, to perform to him that night. And I didn’t even know if they would. But that was when I got this sneaky idea. I was like, but he’s asking for special treatment because if he went to the box office that day, there would not be tickets. So he needs us to sell him what we call our emergency seats, and he needs four of them, and he needs them only four hours before the show. So if he’s getting special treatment, we have the right to give him some special treatment.

And that’s when I literally just pulled out my iPhone and I wrote a speech: “Vice President-Elect Pence, we are the America of black people, Hispanic people, Asian people, brown people, gay people, women and men who are afraid you will not represent us and protect our inalienable rights.” And then we got the cast on board, and we made this decision that we would give him this speech at the end of the performance. And when Brandon Victor Dixon, our friend and a fantastic performer, gave that speech, we had all of the TV cameras at the back of the theater, and I even told Brandon to tell the audience to take out their phones and record it. And that speech became the news that weekend all over America and the world. But in any event, that was our way of engaging in peaceful protest. It was our way of saying, “this is not normal.” And it was our way of expressing some agency over our lives. I knew that this would also be a marketing bonanza. It served all those goals.

Charlie Melcher:

I mean, the show itself in a way represented a vision of America that’s the one that so many of us understand to be what was is in the constitution, what is the definition of a liberal democracy or a functioning democracy, and there was something that really caught the world’s attention with the message, and how it was conveyed in Hamilton. It plays a role defining a period. It was the Obama musical. I think he even claims to have—

Jeffery Seller:

He claimed that he did the first workshop because in fact, Lin had premiered the first song he ever wrote for Hamilton—”Alexander Hamilton,” the opening number—he premiered it at a poetry slam at the White House in the spring of 2009.

Charlie Melcher:

Right, so Obama claims some executive producer—

Jeffery Seller:

Ownership, yeah. Yeah. I love that. You know what, Charlie, what you’re bringing up is this incredible…First of all, what it captures so great is that it shows America then through the lens of America now, through our vocabulary of today, through our look of today, through our diversity of today, through the musical vernacular of today. But what it is is an expression of our greatest impulses, and it manifests our great values. And I want to make it very clear: It also shows conflict. It shows infighting, it shows anger. It is a kind of story that Republicans can embrace just as strongly as Democrats or libertarians or independents or anarchists, because it’s ultimately about this young band of leaders who disagree vehemently about how to make a nation and fight it out and get in the room—if I can say, the room where it happens—and make a compromise.

Charlie Melcher:

You have a very enlightened philosophy, I think, about working with talent. I didn’t know about it really. I was even a little surprised when I read how you approach it in the book. Tell us about how you think of your role in relationship to working with talent like Jonathan Larson or Lin-Manuel Miranda.

Jeffery Seller:

Yeah. One of the stories that I most enjoy from my writing the book was me making them lunch because it’s such a nice start, which is nurturing. There was a moment in time where Lin and Tommy and another artist that we were working with at the time came out to my house to work on Hamilton for two days. And the idea was, just let them work, and then while they were working all morning, I made lunch in the kitchen and then we all got to eat lunch. And it reflects, both functionally and theoretically, my notion of nurture the artist. Be there for them to give praise when necessary, to give encouragement when necessary, to allow them to blow steam off when necessary and be there for when they say, what do you think? Because it is the job of the producer to be able to glean: when do I make a recommendation or a suggestion?

When do I give a criticism and how do I convey it? And of course, one of the things I say is, why don’t you wait until they ask? Because if we wait until we’re asked, they’re going to be more likely to listen to what comes out of our mouth. Because they asked for it.

And sometimes it’s painful, because I also tell the story in the book of me seeing the very first ever reading of Rent that is at New York Theater Workshop that Jonathan puts on. And this reading—first of all, there’s no air conditioning, so it’s like 90 degrees and the reading goes on for three hours. I bring two people with me to the reading, hoping that one of them, them I know wants to be a producer. And I know he’s very wealthy. I’m thinking in the back of my head, my strategy is, well, if I get this guy interested, he’ll come on with us and be our first investor.

He leaves at intermission. Giving us that Australian: “Well, I didn’t know it was this long. I have some other appointment—” But what he’s really trying to say is, “I can’t wait to get out of here as fast as possible.” And the other guy, waits till the end of the show to tell me, “well, Jonathan is very talented, but should just work on something else. This will never work.”

And what had happened is that he had a bunch of good songs and the opening song “Rent” was there, which was like this wallop, and then it just got lost with no character and no plot. A week later, Jonathan’s like, “well, let’s go. I want to hear what you have to say.” And we go out to Diane’s Hamburgers, for some of us who might remember that on Columbus Avenue, and he’s like, “what’d you think?” And I’m like, “Oh God.” How do you say it? How do you say it?

And my first advice is: lead off with a compliment or two, and then you have to find a way. And after I say how great those first songs, “Rent” was, and stuff, I said: “But I can’t follow the story and I can’t follow the characters. I’m not connecting to any characters, and I don’t understand the plot.”

I said, “do you want to write just one of those collage reviews of life in the East Village or do you want to write a story?” He said, “no, I want to write a story.” I said, “then you have to go to find the plot.” And he was taken aback and a little bit angry—or defensive, maybe that’s the better word.

Charlie Melcher:

That’s a better word.

Jeffery Seller:

And he went away and got to work.

Charlie Melcher:

Jeffrey, when was it that you realized that you needed or could trust your own instincts, that it was up to you to use your own…?

Jeffery Seller:

Yeah, you just reminded me of something. So how do we become critical? And I mean that in the best sense of the word critical, using our critical faculties, what supposedly they’re trying to teach us in undergrad, getting our BAs in English or anthropology or poli-sci. I mean, for me, I can put my finger on two moments of time. One is, I’m a teenager and I’m in my youth theater group and I’m in a play that I don’t think is very good. And I raise my hand and I say, “who picks the play?” And they say, “the play reading committee.” So I become a part of the play reading committee and then the chairman of the play reading committee. So I start reading a lot of plays when I’m 14 and 15. And as you start reading a lot of plays, you start having an opinion about what’s good and what’s not. And then if it’s not good, why? So I start that as a teenager. I continue that as a student. And when I start directing in summer camp and then the student shows at the University of Michigan, I’m gleaning more about that five-act Shakespearean structure. About exposition, major dramatic question, rising action, conflict, tension, right? Point of no return—and that was the first time I ever started engaging in that process, which I learned to be called “dramaturgy.” Terrible word, essential task.

Charlie Melcher:

I just find it an interesting lesson for people in any creative field, really, any kind of storytelling. When do you go from being the student or the dutiful employee or the supporter to being able to realize or feel confidence in your own instincts and your own judgment and being able for you to switch from working for somebody to being able to lead.

Jeffery Seller:

But you know what, I want to say of something else, Charlie. As I’ve gotten older, I’m less sure of myself.

Charlie Melcher:

Ah, that’s interesting. Why do you think that is?

Jeffery Seller:

Because one has to be open to the fact that something might work and not comply with the traditional structure. That there are other ways into storytelling. That every story does not have to have that same structure. Once in a while, I’ll see a show or something off-Broadway, and I’m like, “that is not going to work.” And of course I’m right, but I am more modest with my strong opinions as I’ve gotten older.

Charlie Melcher:

Maybe that’s just some natural wisdom that comes.

Jeffery Seller:

Yeah, like, I don’t know what’s going to work.

Charlie Melcher:

But you also, you were the radical young upstart, and now you are the establishment.

Jeffery Seller:

I have to admit it, I’m now 60 years old. I’m not 31 doing Rent as the upstart who with his friend, Drew Hodges, created an ad campaign saying, “don’t you hate the word musical?” Because we just had to. That’s who we were.

Charlie Melcher:

I’m aware. I also remember some years ago, us talking about immersive experience and storytelling that’s not necessarily linear, that breaks with a proscenium, the fourth wall, where the audience is a participant. And I remember you being very… “Ooh, that’s not for me. That doesn’t sound comfortable, or I’m not interested in that…”

Jeffery Seller:

Yeah. Well, it is true that I turned down being a producer of and then an investor of Sleep No More twice. Not once, twice. And you know what? But I want to also say: I produced De La Guarda, which started this whole thing in 1998. Right? We did that a long time ago. An immersive experience where the audience stands up and the show takes place in the air above your head for 105 amazing minutes. And though we ran for over four years in New York and we did a bunch of other productions, it never could figure out how to make money. Because the cost of running the show was so high. So when they brought me to Sleep No More, I was like, “you’re never going to make money.” It might be a good show, but I just don’t think you’re ever going to make money. And—okay, how wrong I was. I live to watch them be phenomenally successful, but I didn’t get it. And frankly, when I went to see Sleep No More—and by the way, I’m going to see their new show tonight, which I look forward to—

Charlie Melcher:

Me too.

Jeffery Seller:

I thought it was just the most amazing adult haunted house I’d ever been in. That’s what I thought. I thought, oh, they’ve figured out how to make a haunted house for adults, and it was ingenious. So I can’t get everything. And that’s okay.

Charlie Melcher:

You’ve done okay.

Jeffery Seller:

Yeah.

Charlie Melcher:

Well, Jeffrey, this has been just a joy to get to catch up and for you to share so many wonderful stories so openly. I want to encourage everyone to read your book. There’s more of them in here, and I just can’t wait for the next 60 years of your productions and your nurturing of talent, and you’re using your incredible taste and judgment to bring wonderful stories to the world. So thank you.

Jeffery Seller:

Well, Charlie, storytelling is still everything to me, and I want to make another good musical that has great storytelling. I still want to make another good one.

Charlie Melcher:

Can’t wait to go see it.

Jeffery Seller:

Thank you.

Charlie Melcher:

Thank you.

Once more. I’m Charlie Melcher, and this has been The Future of Storytelling Podcast. Thanks for joining us. The Future of Storytelling is your hub for all things related to creativity, business, technology, and more. To listen to other episodes of our podcast and stay up to date on the latest news from the world of storytelling, check out our website at fost.org. There you can subscribe to our free monthly newsletter, FoST in Thought.

The FoST podcast is produced by Melcher Media in collaboration with our talented production partners, Charts & Leisure. I hope to see you again soon for another deep dive into the world of storytelling. Until then, please be safe, stay strong, and story on.