Ben Shewry: Cooking and Creativity at Attica

About

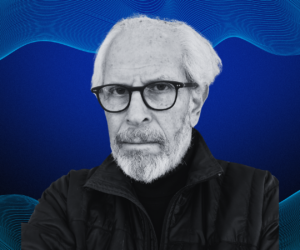

Ben Shewry is a chef, author, and co-owner of Attica Restaurant in Melbourne, Australia. Recognized as one of the top restaurants worldwide, Attica offers guests an experience that immerses them in Australia’s unique cuisine. In his new book, Uses for Obsession, and on this episode of the FoST Podcast, Ben discusses how that experience came to be, as well as his personal learnings on creativity and culture in and around the kitchen— insights which are incredibly applicable to any storyteller.

Additional Links

- Learn more about Attica

- Follow Ben and Attica on Instagram

- Buy Uses For Obsession

Transcript

Charlie Melcher:

Hi, I’m Charlie Melcher, founder of the Future of Storytelling, and I’m delighted to welcome you to the FoST Podcast. My guest today, Ben Shewry, is a world-renowned chef and storyteller. You may recognize him from the inaugural season of Netflix’s Chef’s Table, which featured his restaurant Attica in Melbourne, Australia. At Attica, Ben and his team strive to give guests an authentically Australian culinary experience, paying great attention to every detail from the native ingredients he uses to the locally made plates that his dishes are served on. With this philosophy and a tremendous amount of hard work and tenacity, he turned his restaurant into a global phenomenon. Attica has been included on the World’s 50 best restaurants list since 2010, and featured in publications around the world like the New York Times, the Guardian, Bon Appetit and Eater, who called them fine dining’s “greatest hope.” In his new memoir, Uses for Obsession, Ben describes how he developed his unique voice as a chef and made Attica the success it is today.

As I was reading his book, I quickly realized that Ben’s insights on creativity from the kitchen apply to storytellers of all stripes. After all, making food is perhaps the oldest form of creation known to humankind and sharing food is one of the most fundamental experiences. With that in mind, I hope you savor our discussion about his journey, inspiration and learnings as much as I did. Please join me in welcoming Ben Shewry.

It is a true pleasure to have you on the show. Ben, welcome to the Future of Storytelling.

Ben Shewry:

Thanks, Charlie. What a privilege.

Charlie Melcher:

So I wanted to start by asking you to describe what it’s like to walk into your restaurant. What is your guest experience? And I ask in part because I have to confess, I haven’t had the pleasure yet of coming and dining with you, and so I want to kind of paint a picture of this multisensory experience.

Ben Shewry:

So the building is an old bank. It’s pretty lowkey looking building in a small suburb called Ripponlea of Melbourne, Australia. And as the guest arrives, there’s a big wooden door which is very beautiful and it’s made from a native Australian timber. The actual handle is cast in bronze and that’s cast with the imprint of the bark, of the timber that the door was made from. So that’s the first touch and there’s obviously somebody there to greet you with a very big smile and a very genuine warm welcome. The dining room is filled with art, and some of them are representing the culture from Australia or New Zealand or an artist from America that we love. You’ll be sat at a table, potentially made from Harcourt stone. The stone is from only two hours away from Attica in a place called Harcourt. Every detail in the dining room has been thought through, including the carpet which was made 45 minutes from the restaurant.

It’s very, very considerately lit. That’s crucial. But what we do want to do is disarm our guests who are coming for the first time. Some people arrive and they can be quite nervous. They expect us to be some sort of fine dining temple of gastronomy. They might have read about some type of three Michelin star type of experience, and it’s really not like that. Our culture in Australia is a very warm and friendly and the dining experience from a service perspective needs to reference and reflect that so our people are trained and also encouraged to be themselves and to connect with our guests on a human level.

Charlie Melcher:

And what is one of your favorite signature dishes and how did it come about?

Ben Shewry:

I have a very strict kill your darlings policy. That’s how the restaurant has evolved across the 19 years that we’ve been going. We spend a great amount of resources and time, hundreds of thousands of dollars every year developing the dishes and researching the culture around them and training people. And that could take anywhere from four or five weeks to one year to develop a dish and all aspects of the dish. From the sourcing, procurement of the ingredients to the understanding of the food in the cultural context to the development of the things that affect the dish in the physical space, the cutlery, the plate. Often the plates are custom made by local artists individually for a specific dish in our history. I have a great fondness for a dish from 2008 called “a simple dish of potato cooked in the Earth it was grown.” It’s a love letter or a poem to the culture where I come from, New Zealand Māori culture and in particular the hāngī, or the earth oven, where food is buried and cooked in the earth and that’s a symbiotic relationship that food has with the things like potatoes are grown in the soil and then return to the soil to be cooked.

It’s probably the first dish that really spoke of who we are and what we wanted to do, and it was also a new concept for the time because it was just a potato on a plate. There was no meat on the side, and people found that very, very challenging I got to say, but we stuck it out.

Charlie Melcher:

I was reading about this dish in your new memoir, Uses For Obsession, and you have this expression that you say, “what does a potato want to say?” And that that was the inspiration for the study and investigation that led to this potato. What does a potato want to say, Ben?

Ben Shewry:

Well, I think that should be left up to the potato, Charles. It never had its own time in the sun. It’s always just been the accompaniment food in society. We have this strange view of some foods being elevated and other foods being lowly, and I just wanted to say with that dish that a potato is as good as any other food if not better, and it needs to be respected and rewarded for its profound abilities on humans. It’s so delicious in so many ways, but I felt pretty strongly that no potato dish before that truly let potato speak. So everything in the dish is about amplifying the potato and its connection to soil, its terroir, where it comes from, how it grew, and potatoes taste—a really gamut of different ways depending on whether or not they were grown by the coast in sandy soils, or rich alluvial soils in land. If they come from New Zealand or if they come from California or if they come from Australia, they all taste very different or from Peru and seeing it really kind of in a way for the very first time. If we could put aside all of the things in our lives, all of the ways in which we’d considered an object or all the prejudices that we have, all of the things that we’ve been told and just clear them out and they weren’t there anymore and all you were left was with this object, with no knowledge of it, it brings you back to ground zero and it’s kind of a beautiful thing to start from that place. That’s how I try to work mostly.

Charlie Melcher:

You used the term “terroir” to talk about the potato, which is obvious in a way that it comes from the ground, but terroir is a term that’s normally used for great wines, right? For the grapes and the regions that the grapes come from. At least that’s where I first learned that French term. It also seems so fitting for your approach from what I understand, so much of what you try to do is to find the ingredients that are of the place you’re from. There’s so much about the story of place. Can you talk about that a little bit?

Ben Shewry:

The culture that I grew up in New Zealand and rural New Zealand, it was really evident that the truest culture of the place was the culture of the New Zealand Māori people. So that’d been there first before the England invaded New Zealand. And so this history was always there and my mom and dad always taught us about it, and we had experiences with Māori friends and visited the marae, the local meeting place. And so I’ve always understood from the youngest age that the truest cooking that I could do was the cooking of the ground of which I was standing on. And to me, no matter where I am in the world, that begins with asking the question of who were the first people. It doesn’t matter if I’m in San Francisco or if I’m in Melbourne. That’s kind of what I want to get to because that to me is always going to be the realist interpretation of the place that you’re at.

But in Australia for example, we have this amazing culture of Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islander peoples who have been here for time immemorial, the oldest living cultures in the world. And with those cultures come of course tens of thousands of years of cooking, of celebrating, of art, of conversation, of farming and of cuisine, and so it’s a folly to ignore that history. As I started to work with these foods in the early years of Attica, I began to learn that this culture connected to these foods and stories and ways of cooking, and so this is, along with my deep interest and ambition in creativity, is something that informs me and in many ways is essential to anybody cooking on this continent.

Charlie Melcher:

I would love it if you could just describe a little bit some of the ingredients that are indigenous or authentic. There’s not 10 cookbooks telling you how to prepare this or that ingredient, so just give us a sense of what are some of those ingredients that you’ve had to master?

Ben Shewry:

Well, if you think of a restaurant like ours, we are taking raw materials and then we are manufacturing them into things. To your question, these materials are often in our experience, precious and rare, and I’ll give you the example of a native bee honey that we have here called sugarbag honey. Sugarbag honey comes from the stingless Australian bee. It comes to us from about 45 individuals in the northern part of the country in northern Queensland and the Northern Territory. But with this honey, the way historically, and to this day this honey has been hunted is that the hunter would look for the bee flying in nature and may then track it by using a method of one of two ways by sprinkling water on the bees as itflew by to slow it down or to catch a bee, to put a tiny little bit of wax on its tail and then release it.

Now the hunter can follow that bee back to the hive, which is generally in the rotten part of a tree trunk or a piece of wood, and it becomes indescribably delicious actually, that honey doesn’t require us to do anything to it as cooks. We serve it in a small wooden handmade spoon. In this way, chefs can be storytellers. I would clarify though that we must have permission to share these stories, so I always seek permission of the culture that these stories come from before passing them on. That’s just the culturally correct thing to do in Australia, and I’d assert any part of the world. Of course, we make up our own stories on dishes as well, like there’s many dishes that have come through time and Attica and some of them have been quite traumatic, like—I nearly drowned three times in my youth. My father saved me on two occasions. And I created a dish about drowning as one of the earliest expressions of myself in about 2007. Now nobody really needs to eat a dish from a chef about drowning because I’m actually trying to make the person that’s eating that dish have that sense of ocean and sense of being kind of tossed by waves and held down, which is a deeply unpleasant thing of me to do, I should say, Charlie.

Charlie Melcher:

Exactly. You don’t really want someone to have that experience, but what a powerful source of inspiration. Clearly. How much is your creativity as a chef grounded in your own life experience?

Ben Shewry:

Hugely. I had an incredible childhood. Probably the most formative part of my childhood is growing up with a mother and father that loved us very much, and also who were usually creative. My father is an artist. My mother is a very artistic person. That is such a gift to grow up in that environment. We didn’t have any money though. Very little. And this sense of the world and the experiences of a child where my creativity actually comes from, it comes from creativity as a necessity for life and a necessity for just your human existence, but also as a child, as all of your fun and joy is coming from what you can do with the things around you rather than the things that might be brought for you. And so that’s so influential on me today. Creativity has always been a necessity for life for me. I think if you took that away, I’d be crushed.

Charlie Melcher:

We think about learning of history through books or maybe documentaries, but it seems to me that you’ve been teaching a lesson about an indigenous history through your plates and even of the evolution of its social relations by making food that is based on the ingredients that are authentic and true as opposed to maybe dishes that were imported that had a kind of cultural imperialism associated with them.

Ben Shewry:

When you move into a culture and study it and are influenced by it and are given many gifts from it by mentors and friends and elders, you have a responsibility to respectfully pass those stories on. One of the things that’s vitally important to us at Attica is the ability to share this positivity and this beauty with our guests when we have permission. So we do a variety of small things on the tables in the dining room as a guest sits down, there was nothing but a small handwoven basket made by the Tjanpi Desert Weavers. It’s a beautiful tiny artwork that has emu feathers woven into the rim of the basket. Inside the basket are these round seeds that are dimpled, which are called quandong seeds. They’re very tactile. We put that basket with those seeds on the table. We don’t say anything to the guest about it, and inevitably the customer or the guest sits down and immediately goes to the basket with their hand, puts their hand in, because we’re inquisitive beings, humans, we are innately curious.

And so they play with these seeds, they pick them up, they touch the basket, and then they ask the question, what is this? And this practice of placing this basket with these native seeds on the table is our way of just trying to provide the smallest spark to the guest who 99% of the time will not know what either of those objects are. And then we can say, well, I’m glad you asked. These are the seed of an incredible native fruit called quandong, and this basket is made by an artist from the collective of the Tjanpi Desert Weavers, and here we are, and this is what we’re about.

Charlie Melcher:

I can’t help but think, Ben, as I’m hearing you describe that, that there are experienced designers and theater people who have so much to learn from you. How do you draw curiosity or leave space for it or put something down that you know that someone’s going to reach out and touch? You didn’t tell them to touch it. You didn’t tell them you have to learn this. You simply put this extraordinarily woven thing in the center of the table, and now it’s their question and their interest to ask.

Ben Shewry:

For me, that experience of coming to my restaurant is really about us trying to understand the psychology of people as well and the psychology of the diner, and in the ways in which you can create moments of joy for people, but also moments of education and pride. All of this whilst satisfying my own strong creative urges and needs, but always bringing in a large range of collaborators and artists and employees and makers and cultural people because it’s just so much stronger in that way. It’s egotistical to think that any one creative person can kind of do it alone. Nobody can. You need collaborators. That’s where the joy is. I don’t think the joy is even in the completed object. It’s really about the way in which you’re learning to make something. And that journey from the first idea to perhaps a finished dish or product.

Charlie Melcher:

Tell us how you found your voice as a chef.

Ben Shewry:

Very slowly. I guess I’ve always felt different. I’ve also always felt like an outsider. When I ended the kitchen, it was an angry, violent place. Very misogynistic. Not friendly to women. And I thought that it would be a home for me immediately, but what I’ve soon realized was that because I didn’t fit into the stereotype at the time, which was an angry male, I was punished for it really, for being sensitive. It really probably wasn’t until I began at Attica in 2005 that I actually had the opportunity to start to find my voice.

That said, though, along the road, it wasn’t all immense hardship. There were always people that saw something in me and allowed me a little bit of creativity on the side, and I’m incredibly grateful to those people. But it wasn’t until Attica that I started to really kind of put down my own work for me. Just slowly across time, probably three or four years into my tenure at Attica, I’d say around 2008, I started to begin to think that I was developing a vocabulary in cooking that was mine and didn’t feel like somebody else’s.

Charlie Melcher:

And that journey with Attica—it was an instant success from day one, huh?

Ben Shewry:

[laughter] Oh my goodness, Charlie— you’ve read the book, so you really know that that’s a very funny statement. No, no, unfortunately not. I wish I could say that Attica was a restaurant that people very much hated initially. It had been a restaurant before my time and it was failing chronically. It had somebody running it that didn’t know what they were doing, and I came along at 27 and didn’t really know much better either. So it was sort of worse than a new business because it had business that existed for about a year and a half, and it wasn’t great. So everybody sort of thought, well, that’s no good. And so you have to spend many years trying to turn that around. And as I was like any other young creative person just completely and utterly lost and just thinking that my creativity would get me through, and of course it didn’t.

So there was many painful years and many years of near bankruptcy. But I think the main takeaway from that is just you just have to keep going. It’s a cliche to say you have to put one foot in front of the other, but you just have to grind through those hard times. And we’ve been through all of the hard times through the GFC, through the world’s longest lockdown—284 days in Melbourne— through this current cost of living crisis. We’ve been through all of the times. One thing I know more than anything is you have to continue to have courage. You have to be fearless. You have to continue to create in a hard time. And if you can find some way of investing in it, because when things get tight in business and with creativity, people are looking to you. If you’re any kind of a leader or you want to be a leader, and therefore, in that hard time, you actually have to have probably a better or more urgent creative output than ever.

I almost have a sick part of my personality, which quite likes it when things go wrong. It generally presents a brilliant opportunity for change, because when things go wrong, everyone’s listening, Charlie. And when everything’s going right and you want to change something, everybody, the team or society, is like, “why would you change that? Everything’s going so brilliantly.” And people are sort of more stuck in their positions. But when everything goes wrong, there’s a real reckoning and a questioning of everything, and there’s a brilliant moment right there for some real creative thinking and some great outcomes.

Charlie Melcher:

I mean, it’s forest fires that sometimes that open up the pine cones and release the seeds and the seeds for the next great redwoods. There’s a model there in nature for adversity leading to new growth. It’s very true. So the book to me really does seem in many ways to be a story about discovering one’s voice and fighting for one’s creative freedom and ability to express themselves. You have an expression that I’d never heard before in the book, which means something to you, and I’d like you to explain it. It’s called, “the onion is invisible,” and I think it came to represent something about the dogma of classic technique. Can you explain what you mean by that?

Ben Shewry:

Yes, I can. So it’s in early nineties. I’m 16 years old, and I’m at trade school, which is run by a very, very intense, angry and serious group of male chefs from Europe who were very disenfranchised with their lives. They’d got stuck in New Zealand somehow. They’d worked in the great restaurants in Europe, and they were stuck in this country, which at the time didn’t really care about them at all. So they wound up teaching students at the school and they were taking their frustrations out on us. They were treating the classroom like a Michelin-starred restaurant. And I came from tiny school in the country to this college, and it was just a baptism of fire. There was this moment when my tutor, Beet, who was Swiss— we were making a rice pilaf and I’d finally diced the onion for the pilaf— pilaf’s made from butter, onion, stock, rice. He said, you must cut the onion so finely, it’s smaller than the grain of rice and you cannot see it otherwise, it doesn’t work, it’s a failure. And he had said, “the onion must be invisible.” And so I followed his instructions and I made this dish, and he came behind me and leaned over my shoulder and whispered in my ear, “Beautiful, the onion is invisible.” To me, though… why should the onion be invisible? He’s saying this to me like, this is an absolute, you should never see the onion in cooking. The onion is a dirty, lowlife vegetable that should never be seen. It’s so offensive that you can use it to flavor things, but the onion— the onion has no place in cuisine. This was a very much a French dogma, and the expression is important because I think it’s in that moment that I realize that, heck, I don’t really see how I fit into this cooking. This doesn’t represent me or the country where I come from. I like onions. Onions are glorious. So it’s just a funny moment when if you as a creative person or a human just blindly follow tradition, it’s going to lead to you missing out on a lot of things and potentially a lot of problems because I couldn’t imagine cooking without onion being a feature of it in a way.

Charlie Melcher:

You also talk about this idea that you need to learn the basic techniques in order to be able to and how things have traditionally been done in order to be able to, as a creative person, to go on to subvert them. And it seems like you did that, right? You paid your dues, you learned how to make an onion invisible. I’m reminded of Picasso who talked about having to learn classic painting before he could go on to do abstract expressionism.

Ben Shewry:

I think you need to learn the rules before you can break them in a nutshell, Charlie, I think, in cooking— but I would say that this is the same for anything. You need to completely submit to a rigorous level of understanding of almost all of the angles of the thing that you are wanting to do. And in cooking, there’s no shortcuts. It takes a minimum of 10 years of absolute and continuous focus on cooking to get any good at it. It’s just a reality. Then, only then, if you’ve really dedicated yourself really, do you have the ability to start to change things to subvert them. And as I write, I think that reasoned understanding and depth of knowledge of a subject is so central to a human’s ability to change anything, whether or not it’s cooking or whether or not it’s power structures or whether or not it’s another artistic expression. I think some of the most damaging work is done when people rush in with the arrogance to say, “I’m just going to change everything. I’m going to burn the house down.” And they don’t pay homage to all those tremendous people that came before them. It’s just about respecting the culture of the art or the occupation in which you endeavor.

Charlie Melcher:

What is there that you’ve learned from writing recipes that was transferable to writing a memoir?

Ben Shewry:

Well, that’s a really great question. Recipes are the most direct and honest form of writing that exists. If you think about that statement, you think about reading a recipe, it’s like, one cup of this, and then it’s, do this exactly the way that I tell you to do it. And so there’s very little fluff in a recipe. And of course, my whole life has been dedicated to writing recipes. So with the writing of Uses For Obsession, I’ve tried to take some of that directness and honesty and really make it the foundation of the book. In my opinion, the purpose of writing is to tell the truth. And anything other than the truth is disrespectful to writing and its history. And so I’ve really tried to write something that’s honest and truthful and far from perfect in all of the issues and stories that I write about and talk about.

I’m trying to own my own culpability in this situation, and we almost always have culpability now whether or not we want to admit it or not. So for me, it starts with this truth, starts with looking at myself and thinking, how have I stuffed up here and what happened and what was the outcome? So it is kind of in a lot of ways, that’s the book. And also another thing that I strongly believe is that many of the problems that humanity faces deeply entrenched simply by a lack of imagination. And so in the largest sense, I wanted the book to be about the ways in which we can use imagination and creativity to solve problems.

Charlie Melcher:

Yeah, again, that’s what I took that from the book. I found it very inspiring for anybody who’s a creative person because you are really talking about what it takes to fight for that creative freedom to express yourself, and the belief, the optimistic belief that that kind of imagination and creativity can change the world.

Ben Shewry:

And I think without people showing us the way or how it could be done differently, we’re sort of stuck. We should be bringing up people with us as well if we have the opportunity and promoting them and sharing their stories. I think it’s so crucially important. There’s this feeling that we get at the end of a creation of a dish at Attica. So we’ll be working on a dish over and over and over and over and failing and trying again and failing and trying again. And this is how it goes. This is our creative journey. And there’s a moment though when the work suddenly clicks together and is completed, and this feeling with our team of standing around and looking at this thing that we’ve made, this dish that we’ve made, and it’s complete visually textually, but most crucially, the way that it tastes and you taste it, and this euphoric hit just hits your entire body and your entire being. And I always think that this moment, which is just transcending in my life, it is such a beautiful thing to be sharing with a group of other humans. Everybody smiles and beams and we’re like, oh, wow. It’s not a celebration of your own work. It’s like your excitement that you’ve achieved this task that you’ve set out to do, and now you can share it with other humans in the hope that they feel the same way.

Charlie Melcher:

That’s a beautiful place for us to stop, and we, all of us have that experience of standing around that plate with that glorious potato when it’s at that perfect moment, when it’s become the protagonist and it’s perfect, and we are all able to take a bite together and have that glow of joy and satisfaction, accomplishment. Anyway, Ben, thank you for the beautiful stories that you’ve shared in your memoir Uses For Obsession, for the extraordinary work that you do at the restaurant and for being on the podcast with me today. So thank you.

Ben Shewry:

Charlie, it’s such a pleasure. Thank you so much.

Charlie Melcher:

I’m Charlie Melcher, and this has been the FoST Podcast. Thank you for listening. To learn more about the future of storytelling, check out our website at fost.org. There you can find more episodes of the podcast, sign up for our free monthly newsletter, and learn more about our annual membership community.

The FoST Podcast is produced by Melcher Media in collaboration with our talented production partners, Charts & Leisure. I hope to see you again soon for another deep dive into the world of storytelling. Until then, please be safe, stay strong, and story on.