Kaitlin Yarnall: Return on Impact with National Geographic

About

The mission of the National Geographic Society is to illuminate and protect the wonder of the world. Chief Storytelling Officer Kaitlin Yarnall, her team, and the storytellers they fund aim to achieve this goal by telling the right story in the right way to the right person. On today’s episode of the podcast, Kaitlin shares insights on impact storytelling from one of the biggest scientific and educational nonprofits in the world.

Additional Links

Transcript

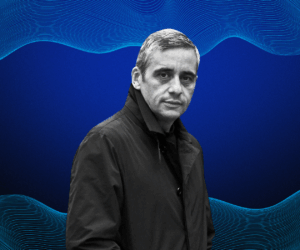

Charlie Melcher

Hi, I’m Charlie Melcher, founder of the future of storytelling. And it’s my pleasure to welcome you to the FoST podcast. The mission of the National Geographic Society is simple: to illuminate and protect the wonder of the world. Since 1888, it’s been pursuing this mission through exploration, education, grant making, and not least of all, storytelling. I don’t know about you, but I grew up with a shelf full of the iconic yellow bordered National Geographic magazines. Their extraordinary photography and writing sparked my young imagination. Today’s guest, Kaitlin Yarnall, has been with National Geographic Society for almost 20 years, and has held many positions including Executive Director of the magazine. Now, as chief storytelling officer, she oversees how one of the largest scientific and educational nonprofits in the world furthers its impact through stories. For Kaitlin, her team, and the storytellers they find, illuminating and protecting the wonder of the world is a concrete goal that they aim to achieve by telling the right story in the right way to the right person. If you’re someone who wants to make a difference through media, you’ll want to hear the insights that she has to share. Please join me in welcoming Kaitlin Yarnall.

Charlie Melcher

Kaitlin, it’s such a pleasure to have you on the Future of StoryTelling podcast. Welcome.

Kaitlin Yarnall

Thank you so much for having me. I’m delighted.

Charlie Melcher

This is really fun. And it feels like it’s a long time in the making. And just so delighted to have you with us today. So I thought I might start by asking you this question about how National Geographic has kind of evolved. And I understand it’s really sort of two parts now. Tell us about them.

Kaitlin Yarnall

Yeah, sure. Absolutely. A little history, the National Geographic Society is 135 years old. We have always been a nonprofit organization, always headquartered in Washington, DC, never affiliated with the government. And we would have always been an organization that supports exploration and grant making. And our evolution really became from a group of people who wanted to give grants and explore the world and discover things. And then they found a way to communicate those two were a little bulletin they put together that became National Geographic Magazine.

Charlie Melcher

Which we all grew up with. And I, my grandparents had the entire run of it, it was incredible. And just like, early introduction for me to the whole idea of storytelling and words and pictures.

Kaitlin Yarnall

Absolutely. And I think every one of us who works there has a story similar, right and most most of America does. But as as you know, that little bulletin grew into the thing we know as as National Geographic magazine. So did the media empire in a lot of ways. So in 2015, the society expanded its joint venture that it already had with 21st Century Fox, who already was a majority owner of our television, linear channels. So the society could really double down on its impact mission work. So in doing that two entities were created, or I should say, further separated. So all of the media properties, basically, most things you can monetize think magazine, books, travel.com. All of that is held in a joint venture, operated and majority owned at that point through 21st Century Fox now through the Walt Disney Company. So that being said, many of our colleagues on the media side still sit in the same building, we still operate together, it’s still one brand, we still move through the world together. And for most consumers, we are National Geographic.

Charlie Melcher

And just give us a quick understanding of the mission of the society.

Kaitlin Yarnall

Absolutely. So we we use three big disciplines storytelling, education, and science. Our mission statement is to protect and illuminate the wonder of the world. So how do we do that? We do it through something called our explorers. Explorers is a really fancy term for our grantees and people we fund. So we give grants and funding to scientists, conservationists, educators, and storytellers. And they have impact on the world. So unlike other big nonprofits that are focused on number of species or hectares, or books and classrooms, were focused on our talent, and our explorers and how they make impact on the world.

Charlie Melcher

Tell me more about this idea of calling storytellers “Explorers” and giving grants and money to support their storytelling. How does that work?

Kaitlin Yarnall

So as part of this transition away from, you know, being hands on in the media company, I myself transitioned– I was on the magazine staff, I moved over, or I should say, stayed with a nonprofit, but left my media team behind and really sat down and said, Okay, how do we within this framework of, of supporting explorers? How do we move in the storytelling space? So one of the things I’m most proud of is we are now the largest grant maker to individual storytellers in the world. Wow. So photographers, filmmakers, writers, cartographers musicians, and their grants from $10,000 to multi million dollar multi year investments. And it felt silly to come up with another title for them, they are explorers, they are they explore the world, the same way that our scientists do. So you know, and we treat them the same. So these are our frontline eyes and ears on the world. And we gather them and we publish their work. And they are how we have impact in the world.

Charlie Melcher

Amazing. So I think about places like publishing companies or film companies who may be investing in a storyteller for commercial outcome, you know, you’re gonna publish your book, you’re going to make a documentary, you’re going to make a feature length film, and they don’t necessarily give that many budgets to these types of people. But here you are giving to so many different storytellers. What criteria are you using to decide who gets the money and and how much?

Kaitlin Yarnall

It’s not an exact science, as you know, we but we try to make it as equitable and fair as we can. First of all, we look at mission alignment for us. Now, the good news there is that our mission is about as broad as you could drive a truck through it, you know, to illuminate and protect the wonder of the world. And we do that through many lenses. But you know, they’re as broad as wildlife, human history and culture. Ocean, so So I often tell potential applicants if it feels like a national geographic story, it probably is. So one mission alignment, to we really look at, is this the right person to tell the story? And one, do they have the skills to do it? Do they have the experience to do it? Are they going to be safe doing it? And then also, do they have the particularly telling people stories? Do they have the sensitivity, local collaborators, really reason to tell the story and knowing that they are going to be telling it in a respectful, meaningful, and, and right way. And then also, we ask a lot of questions around distribution and impact. If you get this grant from us. It’s not just to tell a story about a thing, because people need to know, why do they need to know, what is the impact you would like to happen? And so that takes many different forms. Sometimes it’s, you know, I want to make the story because I want to be able to get this on a local television channels so that the people who live in this place know about it, or we’ve seen, you know, the work we funded, be conveyed into public health campaigns. There’s a lot of different examples I could get. But we really look at what’s the story? Is it the right story for us? Who’s the storyteller? Are they the right person to tell the story at this time? And then what’s the impact that’s going to be made? And and how is it going to get out in the world?

Charlie Melcher

Okay, so I want to take on all three of those. First question is about how you… “is it the right story for you”– Is there an example of of a grant you’ve given that helped you expand or redefine what is a National Geographic story?

Kaitlin Yarnall

Yes, so many. This is not your grandmother’s National Geographic Magazine, when you think about the brand and what we do. We’ve given some incredible grants to, you know, a composer I’m thinking of one, her name is Mekhlit Hadero and she did an incredible body of work around her experience as an immigrant, a child of immigrants, from Ethiopia, and what home meant and how that manifests itself in her own family. But she did it all through music, and what that look like and and I think that’s incredible. Why wouldn’t–that is a valid form of storytelling, why wouldn’t we push on that? And when you think about, it’s still a National Geographic story. It’s about migration and diaspora communities and food and culture and geopolitics. It’s all wrapped up. The medium’s different. And really, like, pick your subject, is it–is it media, is it geography, its demographics. It’s been really, really fun, to think about how we layer this all together.

Charlie Melcher

Well, that leads to the next question about, how many people have you given grants to? And what is the kind of distribution of them?

Kaitlin Yarnall

Yeah, and our focus has shifted in the last couple of years. Actually, in the beginning, we were giving a lot, you know, hundreds a year. And once you get a grant from us, you’re always in an explorer. And so they’re part of the community, we are now narrowing. And I’d say we’re probably going to give 50-60 grants this year to storytellers. We want to make fewer investments, higher dollar amounts, and really support these people better. In terms of distribution around the world, I’m really, really happy to say we were at gender parity, we’re funding work on every continent. We still, you know, full transparency, have some gaps in our portfolio of places that we’d love to find some more storytellers to work in. But I’m really proud of our ability to have spread across the world. And while not leaving behind our traditional community of storytellers that I’m very respectful that you know, many of them built the house we sit him. We give a large chunk of grants that are $10,000 each to, we call them our “level one grantees.” These are early career people, their first engagement with us. We give a smaller number, I think 20 or so, that are up to $100,000. That these are our established people we’ve already funded many times. And then we have about, I’d say, eight to 10, you know, programs, grants that are anywhere from 250,000, north of a million.

Charlie Melcher

What role are you playing in this kind of seeding, this just sort of Johnny Appleseed, if you will, of storytelling, that the commercial market’s not solving?

Kaitlin Yarnall

Yeah, I think a couple things. One, what I hear over and over from the storytellers is we give them the gift of time. When you are on assignments, you are paid in day rates, your editor’s like, “either we’ve got a deadline with get it out, or you got four days to get this story.” So oftentimes, it’s you know, they can speed up, they can slow down. And I just find that that gift of time, it delivers exceptional work. So I think that’s one important thing. I think a second probably more important thing is that, you know, these are passion projects, these are things that people really want to do. And so we open up that space. I think the third thing that we’re doing is that we are evaluating and sorting based on impact in the world.

Charlie Melcher

Before I go on to another topic, I wanted to ask how does someone apply for a grant?

Kaitlin Yarnall

Natgeo.org/grants! Or just natgeo.org. I will caveat that they are very, very competitive. I think at this point, it might be easier to get into Harvard than get a grant from us. But we we encourage people to apply. And I don’t want the perception to be that we only give grants to people we know, that is absolutely not true. We are surprised and delighted every grant cycle and you can apply 365 days a year.

Charlie Melcher

Oh, great. Well, I have a feeling we might have more than a few listeners who might be visiting your site and sending in an application.

Kaitlin Yarnall

We welcome that.

Charlie Melcher

How important or is it at all important to explore new technologies for storytelling? Most of the things you’ve mentioned are what today would be considered more traditional forms written journalism, photography, video or film? Are you experimenting in new media?

Kaitlin Yarnall

We are, we’ve done some really interesting AI and VR, AR grantmaking. We have one explorer who I am fascinated by who is basically built a chatbot to tell fictional stories with a reader-user where you can talk with this chatbot, and it walks you through an environmental crisis and climate change, you know, so I think that’s a totally valid form of storytelling and really cutting edge. That being said, I do want our work to go out into the world and to make an impact into the world. So I view it as almost a portfolio manager of the, how much are the things that are the bread and butter, you know, that our own media company is going to run with it that the Times is also going to pick it up? It’s going to be everywhere. I think that’s also part of the National Geographic story that isn’t told enough, that you know, because it is 135 years old, it feels like this stodgy old brand and it can but, you know, Kodachrome was developed on our roof. And we took some of the first remote images of wildlife ever and we pioneered underwater photography and we have a ton of patents for how to typeset on a map and projections in a cartographic space. So for me, it feels like it’s part of the legacy and history of innovating as an institution and we wouldn’t be still alive if we hadn’t.

Charlie Melcher

So let me ask you, you’ve mentioned a few times this idea of storytelling for impact. And I believe you have an Impact Story Lab specifically. Tell me about it.

Kaitlin Yarnall

The Impact Story Lab is a part of my team that’s separate from the grands and programs. And I am really, really delighted with the work that we’re doing there. It is a maker/research lab. We are a team of creatives who produce media, produce stories. But also we have a director of research, who evaluates everything we do. We set out robust metrics for evaluation, we do training for other entities that want it on how to create stories for impact. We also work with academic partners to publish research. I’ll give a couple examples of like, scientists who have an impact they want to make in the world, and they think that media could help them achieve that. And so what we do is we sit down with them and say, Okay, what do you want to accomplish? And really, we work through two approaches, a top down and bottom up. It’s not rocket science. And it’s basic strategic communication, lobbying, advertising, we’re borrowing from other other fields. And it’s really stepping back and saying, Okay, what’s the change you want to make? Who has the power to actually make that change? And then how do we reach them? Can we reach them with media? Is that the most effective tool? And then if that’s yes, how do we do that? And then how are we going to measure success?

Charlie Melcher

But am I understanding that you actually sometimes would make a short film just to show to one or two people and with the intention that if you can get them to change their mind, they can just directly change the policy or preserve that part of the world? Or? Yeah, our

Kaitlin Yarnall

one of our largest programs at the society is run by explore Henrique salah, and it’s called Pristine Seas. And it he’s working to create marine protected areas around the world. And often a film will be made for one president, one environment minister. Now, this film is also presented with a robust scientific case, and an economic analysis, right of here’s why this protected area is good for your country. But we know that humans are not only motivated by their brains, they’re motivated by their hearts, and storytelling gets you there. And so people who come from the media industry or like you’re going to spend how many hundreds of 1000s of dollars for a film for one person

Charlie Melcher

for how many eyeballs to

Kaitlin Yarnall

maybe for maybe he’ll watch it with his kids, you know, like, but I would say instead of return on investment return on impact, right? Like what what is your return, what is the return you want, and if the return is a protected area, and that can be accomplished through spend a million dollars on a film, but it gets you the thing, I’d argue that that is money better spent than some of these things that we know, reach millions of people and that in the dial doesn’t seem to move, right or it moves much, much, much slower. We just this March premiered a film with the president of Botswana, we chose to make a feature film in Setswana. Setswana is the language of Botswana, about 2 million people speak it. Right, that is a very intentional choice, that we are going to screen for a president that we secured weekly broadcast on Botswana public television for a year. And our decision to make the film in Setswana. And to use local crew, because we know that will be better for impact. It’s actually interesting that choices become very, very clear. And for us that was getting it in front of you know the political thought leaders in country and then also getting it to a broad swath of Botswana population. Then, of course, you make it in Setswana. Of course you do. And of course, you’ll hire a composer from there, because that’s the that’s the music you need to hear. And of course, you hire like, you know, the sound guy from there, because he’s going to pick up and know and anticipate sounds in a way that I wouldn’t.

Charlie Melcher

Any other interesting insights or learnings from the world of telling stories for impact?

Kaitlin Yarnall

I would say that transparency is really important for people, you know, there is this fine line of like, storytelling versus journalism advocacy versus documentary versus montage. I think just being transparent with people about your approach, what you’re making, how you’re making it and why you’re making it. There’s some really great research coming out at University of Florida on this as well about emotions and how we use emotions and what those look like and You know, the positive emotions, ah, wonder hope, parental love pride. Really, really, really to scientifically prove proven move audiences more and for longer than that quick like adrenaline, fear, shame. You know, those are like the fast hit. But people don’t want to stay with it. No one likes to feel that way. And so they’re going to run away from your content. So if you see a thing together, I think about your Explorers Club, right? If you see a thing together, that is awe inspiring. It’s like, it creates that collective bonding. Right? So isn’t that the magic of film? Isn’t that why you want to go to the theater? Yeah, they’ve got better speakers and a screen, but also is that collective gasp in awe. It’s why we like live music. It’s why we feel compelled to show people the sunset and watch it together. Right. And so it’s interesting to the other thing I’ve I’ve been thinking a lot about is so much of this is, and I’m no expert by any means. But my any reading you do on like, the evolutionary biology of this, it makes sense. Right? We are. We’re primates with big eyes, were tuned for visual storytelling. We were not meant to be individuals in the world, we move as groups, we were scanning the horizon for for predators and prey, you know. And so I don’t mean to oversimplify, but it’s, we treat ourselves as very different. Right. And I think a lot of this is, is pretty basic and intrinsic. And not that there’s not a ton of cultural difference and nuance, and historical trauma that layers in. But I think that base brain psychology is there. And the other thing I’d say is, I feel like as an industry, particularly in the in the journalism or documentary space, we’ve been pretty precious about things and have been afraid to borrow from advertising, lobbying, dirty

Charlie Melcher

words, stop. I’m putting my fingers in my ears.

Kaitlin Yarnall

Look at some really successful public health campaigns. People don’t smoke like they used to. I can say the word condom and people don’t run away. You know. So you look at this, these kinds of public health campaigns that worked and then some unsuccessful ones. This is your brain on drugs, remember, I mean, I’m a child of the 80s. I remember this right. And so if you think just anecdotally, that appealed to fear, versus some of the other campaigns that appealed to like parental love, secondhand smoke was a huge shift for that. It’s not about you, it’s about those around you.

Charlie Melcher

If this is true, that these positive emotions are the ones that are most meaningful and long lasting and impactful to us, meaning make for change. Why don’t we have a world of storytelling filled with happy, loving, positive stories?

Kaitlin Yarnall

former editor of mine I work for it used to always talk about balancing the wonder and the worry. And I hold that really close. We don’t We can’t gloss over things. We can’t be Pollyanna. On the other hand, there are always heroes, there is always hope. There are usually people looking for solutions. I hope. I don’t, I don’t want to say there’s not right. And so I think so much of it is and it’s hard in a quick, you know, news cycle to do that. I get it. You’re you’re doing the like top of the hour NPR News beat you’re not going to say, but let me introduce you to this one lady who’s got a solution if only she could scale it up, right. But I do think the heroes are there, the helpers are there. And people don’t want to feel helpless, it makes you turn away. And so I think it’s part of our responsibility, depending on what medium you’re in, I have this incredible privilege to have time and resources to say, Okay, this is a dire situation. But what are the solutions that are out there? Who are the people who are working to change this? How can you help whether that’s you President create a protected area, or you parents make sure your kids know this?

Charlie Melcher

I think time is such a key element to this topic that we’re talking about. Because the fight or flight instinct works best when you have very little time, like the nightly news or social media versus these more powerful and longer lasting stories which require more time to tell, and maybe more time to to create and absorb boom,

Kaitlin Yarnall

yeah. I’ve often been asked, you know, who’s National Geographic competitor, especially when I was on the media side? And my answer was, we’re not. We’re competing for people’s time. High like, and I think about that a lot from a creator, but also a consumer perspective of we are competing against every book, every written, every mover movie ever made every cat video on the internet. And so you really, it’s the gift of people’s time. And so that’s how you get people to linger to is to give them something they want.

Charlie Melcher

Are there any trends that you see taking place in the world of storytelling, and you get to see so many different storytellers and their ideas, their passion projects? What’s what has shifted? Or what’s emerging that you can see,

Kaitlin Yarnall

I think there’s a huge, particularly from the individual creator perspective, a huge shift and reckoning on what story should I be telling? And whose story should I be telling? I think COVID and the pandemic really pushed this accelerated it as people weren’t able to fling themselves around the world as they used to. It’s been really interesting to watch some storytellers that I love and admire who used to travel a lot, who are like, you know, what, I found a equally compelling, probably more rich narrative, where I live and where I am. And I’m going to tell this story, because I’m the person best suited to tell it. I’ve seen this manifested in some of the bigger productions where they couldn’t send crew around, and they had to find local crew. And they’re like, oh, my gosh, not only are these guys great, and it reduces our carbon footprint in our budget to, to not fly our people there. But they’re in tune to storytelling in a local context and know the places and the people in a way that we never would you

Charlie Melcher

make me want to ask you about what you’ve seen, or just hearing you talk about this idea of passion projects, and you again, you’re in such a lucky position to be able to get to see people’s real passion projects. What makes for a passion project, I think that so many people, there’s plenty of projects, people are busy, but what really differentiates something that somebody comes to, because they have to because they care so much, not because they’re paid to or they were told to.

Kaitlin Yarnall

I mean, so many people, it’s the thing that can’t get out of their head. And some people it’s related to home. You know, we have an explorer, a photographer and filmmaker who has been working on wildlife corridors in the state of Florida for decades. And for him, it’s like, this is home. I’m a sixth generation Floridian rancher, I like it’s home and we need these wildlife corridors. And so it’s like, he can’t get it out of his blood like it. He was born into it. Some of it’s that but then some of it, I see some incredible examples of like a photographer who did an assignment about childhood marriage. It shook her, she became a different person. And she has now launched a huge nonprofit, and it has become her life’s work. Another one of our photographers who I think it started as an assignment of looking at his gay marriage around the world. And he now has a whole foundation called Where Love is Illegal, because it somehow tapped into their identity, whether that is as a woman, as a mother as a queer person, as a ally, I, you know, I don’t presume to know why or how, but I see people come to it, probably in those two camps. One is either, you know, it is so core to who they are, be it geography, identity, something that is part of their identity. But then, the other one is they see something that they couldn’t shake out of their head. And if you ask most, I think working storytellers they’ll tell you like, what’s the one thing you want to go back to? I’ve yet to see someone like, hesitate. They’ve got their list of like, I went there on assignment, I create a shoot there, I did something. And, man, there’s a lot more there.

Charlie Melcher

Caitlin, you have one of the coolest jobs. I mean, that’s, I’m just so impressed. It’s so amazing that you are in the position that you’re in that you’re able to support such a broad community of storytellers around the globe, and that you can do it, you know, from this place of really wanting to change the world. I mean, I think a lot of people say that, but that’s not what’s driving their decisions. It’s not what’s the what they’re measuring, you know, they’re measuring eyeballs or dollars. And it’s, it’s really special to be able to see that National Geographic is so committed, truly to illuminate and protect the wonder of our world. So, thanks for being on the podcast and sharing some of your wisdom. It’s great to see you. Yeah. Likewise, thanks

Kaitlin Yarnall

for having me.

Charlie Melcher

I’m Charlie Melcher, and this has been The Future of Storytelling Podcast. Thanks for joining me today. This month I’m excited to share that we’re conducting our first ever community survey. Please help us better understand our FoST family and tell us what you’d like to hear more of by visiting the link in this episode’s description. We really appreciate your feedback, and it will help us better serve you. A false podcast is only one of the ways to stay up to date with the latest and greatest in innovative storytelling. We also have a free monthly newsletter and an annual membership called the FoST Explorers Club. You can learn more about both by visiting fost.org The FoST podcast is produced by Melcher Media, in collaboration with our friends and production partner charts and leisure. I hope to see you again soon for another deep dive into the world of storytelling. Until then, please be safe, stay strong and story on.