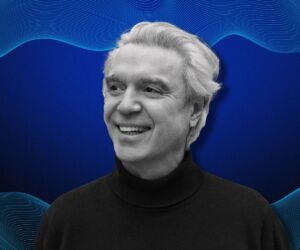

Theodore H. Schwartz: Your Brain is a Storyteller

About

In his new book, Gray Matters: A Biography of Brain Surgery, neurosurgeon Dr. Theodore Schwartz delves into the history and practice of neuroscience. What he and his fellow scientists have discovered is that our lives are based on stories that our brains construct, and those stories are not fact, but fiction. Ted is certainly not the first guest on this podcast to talk about the relationship between brain science and storytelling— but as a neurosurgeon, he comes at it from a uniquely hands-on perspective.

Additional Links

Transcript

Charlie Melcher:

Hi, I am Charlie Melcher and this is The Future of Storytelling Podcast. Welcome.

I was recently reading “Gray Matters: A Biography of Brain Surgery” by renowned neurosurgeon, Dr. Theodore Schwartz about the history and practice of brain surgery. In the book, I was surprised by the number of times that he referred to the mind as a storyteller or writer or our own personal Shakespeare, as he says in the book, in a very real sense, we all have our own built-in personal biographer on retainer whose job it is to keep the timeline of our life stories tight, the plot plausible, and the action moving forward. Only the writing is fiction, not journalism. Here’s someone who has spent countless hours operating inside the human brain and what he and his fellow scientists have discovered is that our lives and our sense of self are based on stories that our brain constructs to help us process our experiences. And those stories are not fact, but fiction.

Ted is certainly not the first guest on this podcast to talk about the relationship between our brains bodies and how we make sense of the world around us. But as a neurosurgeon, he comes at it from a uniquely hands-on perspective. Dr. Ted Schwartz is the David and Ursula Barnes endowed professor of minimally invasive neurosurgery at Weill Cornell Medicine, one of the busiest and highest ranked neurosurgery centers in the world. He’s published over 500 scientific articles and chapters and has lectured around the world on new minimally invasive surgical techniques that he helped develop. Please join me in welcoming Ted Schwartz to the FoST podcast. Ted Schwartz, welcome to the Future of Storytelling podcast.

Ted Schwartz:

Charlie Melcher, thank you for having me.

Charlie Melcher:

I really should say Dr. Theodore Schwartz because that’s who you are.

Ted Schwartz:

That would be totally inappropriate.

Charlie Melcher:

Given that the truth be told. You and I go way back and I feel like we have to be upfront and honest about that in this conversation.

Ted Schwartz:

It’s like a disclosure before you give a talk.

Charlie Melcher:

Exactly, exactly. For our dear listeners, Ted Schwartz is my oldest friend and was my best friend for a very long part of my life, and I feel very blessed to continue to have him as my friend. So welcome my friend.

Ted Schwartz:

Thank you. It’s great to be here.

Charlie Melcher:

So let me start by saying congratulations on your wonderful book: Gray Matters: a Biography of Brain Surgery. I really, really enjoyed reading it.

Ted Schwartz:

Thank you very much. It was fun to write honestly.

Charlie Melcher:

In addition to saving lives as a brilliant brain surgeon, you have also been a writer for many, many years, but mostly that’s been very scientific kind of writing. How was it to write something like this, which is so easy to read, so pleasurable, so informative, a more popular book?

Ted Schwartz:

So there’s two aspects to writing a book in a way. And half of the battle as many people know who’ve tried to write a book, is having the discipline to actually sit down and write a book. And because I have a 30 year history of writing scientific articles, the discipline of sitting down and writing was not hard for me. The other part, making a book readable was challenging, but I also asked for help along the way because I knew that I needed help and I was lucky enough to have so many friends in the industry like yourself and writers screenwriters who I sent the book to, and they would read it and help me edit it.

Charlie Melcher:

You’ve made a beautiful tapestry that covers real science, real history of the discipline, pop culture in ways and very human stories. I was surprised at how many times I was moved to tears in the book by the power of the stories. I guess on one hand I shouldn’t be so surprised because you’re dealing truly with life and death and that’s emotional and it relates to everybody, but also because you were able to be so vulnerable, so honest, share stories of your own that were powerful and moving, tell us one of the stories that you share in the book that was really moving for you.

Ted Schwartz:

For one of the stories that has always resonated so deeply with me happened very early in my career. I was a first year attending, which is kind of that moment where you are no longer operating with a senior person at your side, like imagine a driver’s ed where there’s the driver who can grab the steering wheel next to you and you no longer have the benefit of the safety net and you’re on your own. And I was working in New Jersey at a very busy trauma hospital, which was U-M-D-N-J is what it was called then as a different name. Now it’s in Newark. And so I got a call about a young girl who had been riding a horse and she had a helmet on motorcycle zoomed by spooked the horse, horse reared up, she fell off, hit her head, and by the time I get there, honestly, she’s already on the operating room table because there’s no time.

This is a life and death emergency or a decision has to be made very, very quickly. I can look at the imaging on my phone and just come in, we do the surgery as fast as we can, we evacuate this hematoma. I’ve not met her parents, I’ve not had a conversation with her, and I walked out into the hallway looking for her mother, and sure enough, there’s this woman who looks like she’s just been beat up in a fight. She’s basically collapsed sitting on the floor. I knew exactly who she was the minute I saw her face and I told her what happened. We did everything we could as quickly as we could, but I didn’t know what was going to happen. I didn’t know if her daughter was going to wake up again. And in fact, her daughter was in a coma for many, many, many days, and I would go and round on her and her mother would be curled up in bed with her, literally spooning her in her ICU bed and she just wouldn’t wake up.

She wouldn’t wake up. One morning I went by and she was crying, the mom was crying and I said, what happened? What’s going on? She goes, well, the doctor told me that if she hasn’t woken up by now, she’s probably not going to wake up. I was furious because I had looked at the MRI scan, we did, her brain looked okay, I thought she still had a chance and I would not have crushed this woman’s hope. And I said to her, look, just hold on a little bit longer. Let’s not give up hope. And sure enough, a couple days later, her daughter starts moving her finger, she’s moving her hand, she squeezes her hand, she ends up making a full complete recovery. And I remember going home to my wife as she was waking up and literally sort of saying to her, if I never do another operation for as long as I live, the 20 years of training that I went through to learn how to do this was worth it. Because you sacrifice and you give up so much you don’t know what you’re going to get back. And stories like that really are what move us as surgeons to do what we do because they’re not all victories, right. I and I talk about that in the book. There are patients who don’t do as well and that weighs on us as well intensely. But when you get one of those positives, it just fills your soul with so much hope and pleasure. The pain kind of rolls off your back.

Charlie Melcher:

Have you heard from that family?

Ted Schwartz:

So her mom would send me a Christmas card every year with a picture of her and she would describe all the things that she was able to do, the things that she accomplished that last year. And I would look forward to that every year. And it was just a beautiful connection.

Charlie Melcher:

As a storyteller, I’ve always been so interested in the human experience, how we define personality, how we define consciousness, how we make decisions to operate through the world. I’ve never met anybody who’s been actually as close to the human brain as you have. And when I came across this latter chapter in the book chapter 15, which you entitled, we tell ourselves stories in order to live, I was like, boom, this is us. This is perfect for the future of storytelling. So I’m interested to ask you about how your learnings of working in the human brain have helped your understanding of things like personality and consciousness.

Ted Schwartz:

Yeah, those are very much things that motivate me. As you know, I majored in philosophy in English as an undergraduate.

Charlie Melcher:

Sorry to interrupt you, but I just have to say I remember really clearly Ted when you were leaving Harvard because you were also an incredibly talented musician As we grew up together. In fact, I think we started playing saxophone together at the very same time anyway, you went on to be a really gifted musician and you had that moment where you had to make a decision where you were going to pursue an artistic career or medical school. And I remember that conversation really clearly.

Ted Schwartz:

Right? And I think that’s one of the things honestly, that motivated me to write a book, to have a creative outlet for an otherwise very scientific life. I really want to be an astronaut when I was a kid. And because the idea of traveling to another place that very few people get to go to and experiencing something that other people don’t see, and then coming back and talking about it really spoke to me. And I saw in brain surgery and neurosurgery a very similar life where instead of traveling to a macrocosmic planet, you’re traveling to a microcosmic location in the brain. And I’ll spend my entire day literally living in an area the size of a postage stamp that I’m looking at under a microscope, moving very, very small instruments. But to have that experience and then to come back and to say, okay, this is what we learned.

This is what I’ve observed over 30 years of being in this place, that very few people go. And one of the things that I have spent a lot of time thinking about is this idea of who we are, how the brain creates the mind, the relationship between the brain and the mind. What you see in neurosurgery are unique examples of interacting with the human brain and seeing how that interaction affects the mind that shows you very clearly that there almost is no such thing as a mind. It is not in some way it’s controversial and from other perspectives it’s completely not controversial. I mean, I’m very much a scientist in this and I believe that the brain is really where everything happens and even the self, our identity, who we are is really created in this brain and that we don’t really have a good sense of what the self is.

Charlie Melcher:

I know you in the book talk about some of the people who did these first operations and then studied it. Maybe you could

Ted Schwartz:

Describe that many people are familiar with their split brainin experiments and we think that, oh, the right brain does this, the left brain does this, and we have sort of this popular conception of artistic versus more mathematical. It’s really not that straightforward and not that crystal clear. One of the stories I get to tell that is not heard that much is who are the neurosurgeons who first did this experiment? And it was a guy in the 1920s, 1930s named Van Wain who noticed that his patient with seizures, who had tumors growing in a part of the brain called the corpus scum, destroying the corpus scum, their seizures would get better. And the corpus close is basically this wire that connects the left side to the right side of the brain and he’s like, huh, my patients got better. What if I go in and just cut this?

He had no idea what it was going to do to this patient. It turns out it actually helped them, but it was so iconoclastic when he started doing it that the neurosurgical community did not absorb it as a treatment for epilepsy. I think they felt it was just too radical. So it basically laid dormant for many, many years until another neurosurgeon named Joe Bogan, who was a resident. He was in training at the time, and again, this is the 1950s, the era of the lobotomy where neurosurgeons had the ability to try things without the same kind of oversight that we have now. So anyway, I tell the story of the evolution of the corpus callosotomy and how if it weren’t for the neurosurgeons trying these crazy experiments, the neuropsychologist would not be able to then ask these patients questions and basically insert information in one hemisphere versus the other hemisphere and ask the patients what they are thinking and what they are feeling, and realize that you can insert information in one hemisphere, the right hemisphere that has no language abilities, and the patient can behave a certain way based on the information that’s being processed in their brain that they’re not aware of.

And then when you ask them, why did you just do that behavior? What came over you? They will make up a story. Here we go, making up stories to justify why they behave the way they did. And there’s obviously some impulse. There’s an organ in our brain, there’s something that pushes us to create stories. That’s all. Our identity is a story that we’ve created from beginning to end. And I know you’re smiling because this ties in exactly to what you’re thinking, but neurosurgeons are on your side.

Charlie Melcher:

Well, I thought it was so fascinating that you came to that conclusion from somebody again whose work so deeply in the brain. There’s this quote that I’m going to read from your book. Human Consciousness may be nothing more than what it is like to have a brain composed of multiple subconscious modules that control our behaviors. While another module, Quill in hand becomes our own personal Shakespeare, visually composing compelling if ultimately false narratives to make sense of our behaviors. I thought that was beautiful, but I appreciate this idea that we are not totally in control of everything we do, but our brain is established a way to make sense of it by creating stories that help us get through the day.

Ted Schwartz:

Yeah, I mean there’s even more eerie, spooky experiments that have been done during neurosurgical operations where you can record from neurons in the brain that will become active before you’ve actually made a decision to do a movement. So if you ask someone to move their finger, move their hand, and you record from a neuron that’s involved in that behavior, and then you ask the patient to look at a clock and say, all this is when I decide to it, and then you push the button, the neuron will start becoming active about a second before they’ve even made the decision to move their finger. Their brain has made the decision for them. And the same thing has been shown in language where you record from neurons that are involved in our speech and shown that those neurons are active before we even have made the decision to start speaking.

Charlie Melcher:

So where do our decisions come from? Do we have any understanding of where ideas originate from?

Ted Schwartz:

I don’t think we really do. I mean, I think there are multiple modules in our brain that process information. They sort of predict the future. They come up with models of what’s going to happen. They make decisions as to what they’re going to do. And there’s many of them that get involved on both sides of the brain in large networks that communicate with each other, that come up with these solutions and create behaviors. The question is whether where the self is in there, do we have any agency? Some people think maybe we have agency at least to stop one of them that maybe. But again, where does that come from? What is the substance of that free will? How does it exist that we have no explanation or knowledge scientifically of how that would even happen?

Charlie Melcher:

I’m curious about how they compete these modules in the book, you talk about how they’re processing information from all over the sensor information into your body. They’re trying to make sense of the chaos of the world, and different modules are better at different types of things or processing of different types of information. Who wins? How do we

Ted Schwartz:

Decide? Yeah, so there are sub-specialized areas. Obviously there’s the visual part of the brain that processes visual information and there’s sensory information. There’s all the information coming from your heart and your gut that’s coming up through your parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system. And that’s all being processed by different modules that are calculating what’s going on, trying to make maps and sense of what’s happening, predictions of what’s going to happen next, and then how the organism needs to behave in order to survive because it’s all sort of survival of the fittest. And the idea is that there’s this similar sort of survival of the fittest idea, but it’s all integrated. So the visual information is integrated with what you’re hearing and it’s integrated with what you’re feeling at the moment with your sensory organs and how they’re behaving. And that creates some sort of a model that we work off of. And there can be more than one model and different options at the same time because there’s so much information coming in that you can filter through to create different types of models based on what you’re paying attention to and what you’re not paying attention to.

Charlie Melcher:

I read a book a little over a year ago, maybe it was a year and a half ago by Annie Murphy Paul called The Extended Mind. And I was so excited by that book because she describes all this embodied cognition, all the things that the body is processing and understanding, and I found it to be fascinating for storytellers. She seemed to be describing everything I sort of instinctively knew about why it was so much more meaningful, memorable, and impactful for people to live their stories, to be actively engaged in them instead of passively because there was so much more of their body participating in that experience. And she makes all these interesting points about how trusting your gut is actually not witchcraft or silliness, but actually real intelligence. I mean a certain kind of embodied intelligence. She gave a great example of traders on Wall Street, and the ones that do the best aren’t the ones who have the most ability to analyze numbers. They’re not the big quants. They’re the ones who actually trust their gut and make split second decisions and go with them. And

Ted Schwartz:

There’s different ways to look at that view. One is to say that your mind is extended so it exists in your gut and it exists in your hands, in your hand gestures, et cetera. I would turn it around a little bit and say that that information from your gut, the gestures in your hand are all coming from the brain. The gut information is going to the brain, which is processing the gut and either feeling something that is telling you you should buy or sell based on some calculation. There’s a memory that you have, you’ve been in this situation before, you’ve made an unconscious decision that you’re not aware of that’s going on in these modules, which has made your gut feel queasy. But it’s not that you’re following your gut, that you’re unconsciously have processed information that has made your gut feel queasy. And so it came from your brain to your gut and what you experience because the self experiencing the interoception and saying, oh my God, I feel queasy.

I’m not going to buy this stock, but my brain is unconsciously processed the information. And the same thing with the hand gestures because one of the things they learned when they split the brain is that the right brain would communicate with the conscious self by moving the left hand because the right side of the brain controls the left hand and the left side of the brain, which is where our language is, has no access to what’s going on in the right side of the brain. But if the left hand is doing something, the right brain can see what the left hand is doing and then make a decision. And yes, their mind is in their hand, but it came from the brain. The brain was the one that moved the hand to make that decision.

Charlie Melcher:

You describe in the book something called queuing, and I guess it’s one of the ways that the different modules communicate with each other. Can you describe what queuing is?

Ted Schwartz:

So queuing is very much that sense of hand gestures, right? So if you think about a gambler who is across the table playing poker with someone and realizes that every time that person is bluffing exactly their eye twitches or they rub their ear. So what’s happening is that there is something in that other person’s brain that they’re not conscious of because they’re trying to gamble. They want to win, they don’t want to lose. They don’t want to give away what’s going on that’s making them touch their ear or do something. So it has to do with the way in which we communicate with each other in unconscious ways by moving our hands, or it could be the tone of your voice or your body language, the way you hold yourself in a chair. You’re clearly unhappy by the way you’re standing there, even though what you’re saying is, I’m very happy, I can tell you that you are not happy by the way you’re sitting there. So those kinds of things is the way we communicate without using verbal information.

Charlie Melcher:

Many of us understand that when we do communicate face-to-face with somebody, a huge amount of the information we’re exchanging is not from the spoken words, it’s from all those other microexpressions or body gesture or whatever that from so many years of mapping of what all that means. And I think that’s another argument for the power of embodied storytelling because it’s not stripped down to just words or images.

Ted Schwartz:

Yes. I have another great segue for you in terms of storytelling and hand gestures, which has to do with brain computer interfaces, the idea of having a patient who is locked into their brain. There are some patients who will have a stroke somewhere or be paralyzed in such a way that they cannot speak, they cannot communicate, but their brain is still thinking all of the ideas and they want to tell their stories, but they can’t. They’ve been shut off from the world because of a biological problem. So we now have the ability to implant electrodes in the brain, in the parts of the brain that move your lips or your tongue. And a neurosurgeon named Eddie Chang is sort of led the field in doing this. And in the same way that when you move your hands, you can communicate through sign language. When you move your lips and your tongue, you move it in the same way to say the same things.

And you can teach a computer to take the brainwaves out of the brain and take someone who is moving their lips and tongue in their brain, but they can’t physically do it. Take that information out, put it into a computer, and then the computer can then say their words and allow them to communicate and tell their stories. But what’s even more amazing than that is that the same parts of the face that move the tongue and the mouth to make the words also create smiles and frowns and our facial expressions. And there’s an enormous amount of information in our facial expressions. So we’re not just telling stories with the words. And so you can use that same brain computer interface so that a paralyzed person in a wheelchair cannot only have their words spoken, but you could have a cartoon image or perhaps even a robotic image of their face that expresses their facial expressions as they’re talking. So you can see them smile and you can see their eyes squint, and suddenly all this emotional information that comes out in other ways can also be transferred out of the brain with a brain computer interface. So it’s that same idea of how do we enhance that storytelling

Charlie Melcher:

When we’re talking about brain computer interfaces, is there a chance that we’re going to be in a situation where computers can read your thoughts, where even your thoughts aren’t private anymore?

Ted Schwartz:

A lot of people about that. The idea of hacking the brain, particularly people now who have deep brain stimulators for their Parkinson’s disease, they have a computer attached to an electrode in their brain, and what would it mean if it was activated without them wanting it to be activated for that situation? The worst that would happen is they might move their arm abnormally. I mean, that’s the worst situation, but it’s not really controlling their thoughts. But when you have a brain computer interface that is allowing you to speak, what’s the difference between speaking what you want to say and just thinking and having a private thought? Can you still have a private thought? And the way these brain computer interfaces are designed right now, it’s important for people to understand that they don’t respond to thoughts. It’s not that the person is thinking that they want to say something, they actually have to move their lips or move their hand.

They have to think about movement. We’re really good at getting movements out of the brain. We’re not good at getting thoughts out of the brain. We don’t really understand where thoughts are created and the network behind them. It could be in multiple locations at the same time. So you have to be actually articulating what you want to say and what you want to do to get that information out of the brain. So you can think all you want, all the private thoughts you want, but it’s only what you actually say, what you express, that the BCI will take out of your brain.

Charlie Melcher:

So it’s the taking the thought and turning it into an action to your lips, to your hands. That is how it gets expressed

Ted Schwartz:

At this stage. Yes, it doesn’t mean that in the future we may not understand how those areas that create language produce those words, but for now, we don’t really understand that.

Charlie Melcher:

So the last chapter of the book really is all about this idea of the brain computer interface and the evolution of that. I know it’s also now become very popular. I mean, Elon Musk himself has invested in a company. Neuralink, where do you see this heading and how quickly

Ted Schwartz:

We can now do so many things with a computer, you could literally be a Wall Street analyst moving spreadsheets around. If you could do all your computer work just with your brain, the individual can just think, move, cursor left, move cursor, right up, down. And eventually they can also take text. They can write or text in their minds, and those letters will appear on the screen because if you use the same brain wave to create any motion, that is where these things are going. But they can also be controlling robotic arms. We can also drive cars. Eventually you can teach a car to go left, go right, push on the brake. All of that you can be thinking about. You could be driving a Land rover on Mars all with a brain computer interface if it’s implanted in your brain or flying a drone. That’s what we’re going to see first.

We’re going to see people who are paralyzed having the ability to move robots and work on a computer. But the really exciting thing I think, is if you were able to take a infant’s brain, which is not yet evolved. Now, I’m not saying we should do this, right, because we’re talking about children, but there’s something about the infant brain. It’s incredibly plastic and it will learn how to take in any information that comes into it and then learn how to process it and make sense of it and make a world. So you could imagine putting infrared information in there, seeing spectrums that we can’t see. And if you started at a young enough age, let’s say they’re congenitally blind, so they’re not using their visual cortex for anything else, that part of the brain’s not going to be used, and it’s just lying there waiting for information to come in.

If we could find a way to put different types of information into a plastic brain, we have no idea what we can accomplish, and we have no idea what the experience of that individual is, who’s experiencing those things that we can’t experience. They could hear pitches that we can’t hear in a way, if you had a sensor that could hear those pitches and wire it into their brain when they’re young enough to enhance our senses, but what it’s like, right, go beyond. But the question is what is it like? We don’t even know what it’s like to see the color red. What is it like to see an infrared

Charlie Melcher:

Look? You and I used to collect comic books together. We’re describing daredevil or many other sort of fantasy

Ted Schwartz:

Echolocation, which humans can do. And that’s exactly something that happens. It’s that plasticity that a blind person who can echo locate, they take their visual cortex and they start clicking with their mouth and they hear the reflected echoes of their clicks, and they can echo locate in the world. They’re human beings who can do that. Now, what is it like to echo locate, right? That’s the amazing question. We have no idea, but they experience something when they echo locate, what is that thing that they’re experiencing?

Charlie Melcher:

Another thing that I’ve struck by reading the book is how much of a craft it is that you do every day. There are tools, there’s practice, there’s techniques. You have been a leader in certain minimal invasive techniques. Tell us a little bit about the craft part of what you do. Yeah.

Ted Schwartz:

We stand on the shoulders of giants as neurosurgeons in that we are handed down this canon of neurosurgery, but it is very much a canon that exists in one moment in time. And we learn from our elders. It’s very much an apprenticeship in neurosurgery where you’re literally sitting next to someone and they’re showing you how they do that operation, and you revere your teachers because they show you how to do these things. But then you realize that there are other ways to do it, and that the way they did it was a product of their training and the tools that existed at that moment in time. And suddenly you’re handed new tools and new instruments and you have to say, maybe there’s a better way to do this. Maybe I can do it differently. And when you train other residents, you see it, right? You see people coming up in their training who get it, and their hands just move in a sort of seamless way, and they can manipulate the tissues and other people that you’re like, oh, goodness,

Charlie Melcher:

This. Don’t let this person into a brain.

Ted Schwartz:

This could be an issue. I’m not sure what’s going to happen here with their future.

Charlie Melcher:

Maybe a garage mechanic. And

Ted Schwartz:

There’s also the anxiety, right? And I write a little bit about this. When you first decide, oh, I’m going to be a neurosurgeon, and then you realize I’m going to spend the next 10 years of my life training, what if I suck at it at the end of the 10 years? That’s going to be horrible. I’ve just lost my entire twenties and I’m not good at it. How do I know if I’m going to be good at it? And you don’t. It’s a leap of faith because you really learn how to do it by doing it, and you learn how to do it by doing it on human beings.

Charlie Melcher:

Ted, I think a lot of people use that expression. Well, it’s not brain surgery here. In this case, it is brain surgery that you’ve written about. And one of the things that I thought was so powerful in the conclusion to the book, you bring up the research that was done recently, some survey of brain surgeons and rocket scientists who everyone assumes are on a higher level of intelligence because it’s so complicated. Brain surgery, rocket science, those are the two expressions. And they do some studies with these supposed geniuses, and turns out their level of intelligence to these questions is the same as everybody else. And what I loved about your being willing to share that at the end of the book was it was a statement about humility. Bringing yourself and your profession back down to a human level, to me is part of art. Again, makes you an exceptional person, makes the book really worth reading in that it has this undercurrent of tremendous humility.

Ted Schwartz:

I appreciate that. It was definitely a tone I wanted to bring in because as a brain surgeon, when you’re in the office sitting across from somebody and they have a tumor and they’ve come to you to take it out, they want to know and they want to think that you are the best person in the world to do that operation on them. So you have to be that person. There is an air of arrogance, if I can say that. That has to come into being a brain surgeon because you have to have a bit of arrogance to say, Hey, you know what? I’m going to go into your brain and I’m going to take out this tumor and you’re going to be okay. It’s like, who are you that you can do this thing in a way? But I didn’t want that to come across in the book, that sort of sense of arrogance because there is, we are frail and we are human beings, and I wanted that also to come across just as much. I think it’s important to have humility. What allows us to become better, because obviously if I thought I was perfect and I’m done right, I don’t need to do any better. I’m perfect. But that’s very much not the case.

Charlie Melcher:

Thank you for the work that you do. Thank you for being the wonderful human being you are and the dear friend. So I really appreciate your being here.

Ted Schwartz:

It’s really a pleasure to be here with you. I’m a huge fan of this podcast and you and look forward to growing all together. Yeah,

Charlie Melcher:

Love you.

Ted Schwartz:

Love you too.

Charlie Melcher:

I am Charlie Melcher, and this has been The Future of Storytelling Podcast. Thanks for joining me and a heartfelt thank you once more to Ted Schwartz. At the Future of Storytelling, we look to a diverse range of disciplines. For insight on how to tell better stories, to learn more, check out our website at fost.org. There you can subscribe to our free monthly newsletter and learn more about our annual membership program, the FoST Explorers Club. If you’re already part of the FoST family, please consider sharing this podcast with a friend. We’d really appreciate it. The FoST Podcast is produced by Melcher Media, in collaboration with our talented friends and production partners, Charts & Leisure. I hope to see you again soon for another deep dive into the world of storytelling. Until then, please be safe, stay strong, and story on.