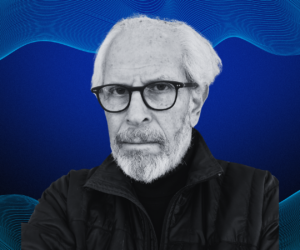

Alejandro G. Iñárritu: Humanity Is First

About

This week, the FoST Podcast is celebrating a very special occasion: our 100th episode. Since early 2020, the show has featured conversations with extraordinary storytellers from a broad range of disciplines, all of whom are pushing creative and technological boundaries and reinventing the traditional forms of narrative. For this milestone, we’re honored to interview Alejandro Gonzáles Iñárritu, the renowned filmmaker behind such critically acclaimed works as Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) and The Revenant. He also created the immersive installation Carne y Arena, which uses VR and multisensory elements to powerfully convey the experience of immigrants at the US-Mexico border. Alejandro represents what we aspire to at FoST: someone who believes in using new technology not for its own sake, but in the service of telling more powerful, empathetic, and human stories.

Additional Links

Transcript

Charlie Melcher:

Hi, I’m Charlie Melcher, founder of The Future of Storytelling, and I’m excited to welcome you today to a very special anniversary event, the hundredth episode of the FoST Podcast. Wow. When I think back over these last three years, I can’t express how grateful I am to have had the opportunity to speak with so many extraordinary storytellers from such a broad range of disciplines, people who are pushing the creative and technological boundaries and reinventing the traditional forms of narrative and media. And the best part has been getting to share their learnings and wisdom with you, our loyal FOS community. Well, for the hundredth episode, we have a really special treat. Our guest today is the celebrated filmmaker Alejandro González Iñárritu. Hailing from Mexico City, Alejandro is one of the most respected and renowned directors of our time. Since his directorial debut in 2000, he’s been creating films with a singular uncompromising vision of our shared humanity.

Some of his most notable works include Birdman, or: the Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance, which won four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay, and The Revenant, which netted Alejandro another win for Best Director the very next year. But Alejandro’s skills are not limited to writing, directing, and producing traditional cinema. He also created the immersive installation Carne y Arena, which uses virtual reality combined with multisensory elements to powerfully convey the harrowing experience of immigrants crossing the US Mexico border. For me, what sets Alejandro’s work apart is how masterfully he draws from his own emotional intelligence and deep empathy to create such rich and unique, yet relatable stories. I think Alejandro represents the best of what we aspire to at the future of storytelling. Someone who embraces new tools in the service of great storytelling, but never at its expense in his work. The technology so seamlessly enhances the narrative that it disappears, leaving us to absorb the meaning on a deeper, more human level. He’s a perfect example of someone who believes as we do in creating better stories for a better future. It’s an incredible honor to welcome Alejandro González Iñárritu to the FoST podcast.

Alejandro, this is an unbelievable honor and privilege to have one of the great master storytellers of our time on the FoST Podcast. Welcome.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

I think that makes me feel very–I don’t know if I’m one of the best storytellers. I do my best, but thank you very much for introducing me like that. Charlie, thank you very much. It is a pleasure to be with you.

Charlie Melcher:

I remember so vividly watching the Academy Awards when you won Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Cinematography for Birdman. And although I didn’t know you personally then, I was rooting for you so strongly because of your talent, because of the original vision of the film, and also because you just seem like such an unbelievably kind and generous and warm person. It was such an exciting moment for me and for the rest of the world as we watched you receive the Oscars and then next year you stepped up there and you win again for Best Director for the Revenant, making you one of only three people in history to do so back to back. To pull a phrase from another famous movie, you must have felt like king of the world.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

Well, it was actually a very strange feeling, to be honest. Birdman was a film that it was very difficult to make. It was very difficult to get financed and because the tone, because it was a comedy, a very absurd comedy, an existential crisis of a man in a narcissistic and all his journey with ego, I never thought it would have much of an attention. It was more an exercise. It was more like a grammatical cinematic experiment that I was really excited– but I never thought that it will get attention the way it did. And then as you said, when it happened for the director award in the next year, I was still shooting Revenant and it was a very challenging physical experience that we were going through and I had to travel in the middle to the award seasons going back and forward from British Columbia and Calgary in Canada. So honestly, I confess that I was actually kind of in another world physically because my mind was in the shooting, my body was collapsing, so I was just surviving during all these kind of, I didn’t know exactly what to say emotionally. I didn’t know exactly what was going on. There was a lot of things, let’s say, flowing in my mind, a lot of agitation, let’s put it that way.

Charlie Melcher:

And at that moment you could have done anything you wanted. You were the hottest property in the field, and yet the next thing you came out with after 2015 was Carne y Arena, this small, one person at a time, virtual reality installation, new VR, new form. I’m just so curious about the decision-making process for you. How did you decide to go from the pinnacle of Hollywood to making this virtual reality piece?

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

It’s very interesting the way you are saying it or the way you are framing it now with the times. You know, looking at your perspective, the way you see it, you are right that I could have done this or that if I will think my career as steps toward fame or money or box office or power. Yeah, I think you are right. It was in a way an unexpected decision, but I had this idea– I was very obsessed with the news about the suffering of the immigrants, and I have been close to them by other films that I have done that touched that thing. And I thought about–my first image was about the feet, the naked feet, the barefoot basically touching the sand and put people in the shoes or in the feet of the immigrant. So suddenly I connect that image with the possibility technologically to do it through VR. And that’s how it started. It was two thoughts that I put together and I started dreaming about. So after Revenant, you are right, I had a lot of credibility. That– it’s a credit that you have sometimes and you lost it very easily. So you are as good as your last film, yeah. So I had that little window, so I was not thinking in box office or a Hollywood thing. I was thinking: how, as an artist, I can get myself into this journey. So it was very exciting.

Charlie Melcher:

Let’s talk about this funny craft of virtual reality and how that’s different than making films. Let me ask, first of all, where did the interest in VR come from? Was there some piece you saw that moved you? What were your influences to want to go into virtual reality?

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

I saw some experiments that were shown to me by different companies for me to be interested, but most of the things that I was able to see was more like video games, a lot of games that you were killing people or you were, things like that. And I was not very interested on that even when it could be fun, but I was not really into it. But I saw the possibilities, but actually there was nothing that I saw that I was like a reference. I think was just the possibility of the technology. One thing I think you mentioned, but it’s important for me to remember, is that after The Revenant, which was a very challenging movie, physically and budget and everything, it’s funny because now it makes sense that I wanted to do something very intimate, and it was me and Chivo. During two years we rented a space in LA and we were actually doing a tiny little film and discovering how to make things, but it was a very almost like a micro independent movie of an experience that we were creating.

Charlie Melcher:

That is Emmanuel Lubzeki, right? Your cinematographer.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

Yeah, yeah, everybody calls him “Chivo,” which is– goat, “The Goat.” Because if you look at him, he has a goat face. There is no doubt.

Charlie Melcher:

I love that you bring him in right away because there you two are two of the most famous– I mean, he had just won his third Oscar for best cinematography in three years in a row, also insane. And so we have two of the geniuses of filmmaking playing with what it means to make virtual reality. And so I’m curious, first of all, what were the things that you ran into that were a challenge? What were the things that you ran into that were surprising or an opportunity?

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

So the first big bingo was, oh my God, we can make people walk around. And the big challenge for that is that then as a filmmaker, you are used to controlling the frame. Each frame is precious, right? So cinema is that little hole that you look through the window, like the key hole that you look through it, and that’s the frame. So when you are shooting a guy in a restaurant, you know that behind the camera there’s a lot of people in the restaurant, but you can create that with sound and the people can just imagine that there’s a full restaurant even when there’s only one guy in front of a chair. But here I have to give the whole restaurant and the whole waiters and everybody has to be in action every time. Suddenly to invent the world simultaneously was really frightening. I had to do a choreography that it was 360 and all the time all of the people were, I will say, main characters. There was no one main character because the people will have the opportunity to go and find what they want to see from which angle, so everybody will have a different cinema experience. So it was super exciting but super terrifying. I didn’t know how to do it. So I will say that that was the first thing that we find out we have to solve.

Charlie Melcher:

I spoke with Tim Alexander from Industrial Light and Magic, who I know you collaborated with, and he used this expression which I loved, he said: at a certain point you realized that you had to abandon the frame and so you had to open it up. As you said, it’s scary, more complicated. I think it’s so interesting too that you talk about choreography because I’ve always been so amazed at some of the scenes that you’ve choreographed in films. Some of your movies feel like they’re all in one shot. It feels almost like the entire film has been choreographed and yet here, this is on another level, right? Because it’s 360, choreographing everywhere all at once. But how did it feel to have to give up control to lose the frame?

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

I call it to end the dictatorship of the frame because it’s a dictatorship. You are locked in this square and it was beautiful because for me, I start everything with theater. I studied theatre for three years with Ludwik Margules in Mexico City, a genius from Poland. He always was smoking his pipe and always he said: “Hey young people, directing– everything is reduced to three questions. Should the actors be sit, should the actors be standing up or should the actors should be laying down? That’s the whole question.” And at that time it sounds like too ridiculous. But then when you are basically in front of two actors or three or whatever is the scene about all those decisions that are almost like a painting, it creates the dramatic tension of a scene and the tone and the space. And this is not what they say. It’s about the silence between the words that really says much more than it, and then where to put the camera– if the camera is a low angle. So all that, I will say, grammar thing, that is just symbols like: where the body stand, the distance, the silence, the angle of the camera. We did almost like a play, let’s put it that way. Right.

Charlie Melcher:

Well, so let’s take a second and just describe what this piece is in case some of our audience hasn’t actually had the pleasure of experiencing Carne y Arena.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

The concept of it is not only VR. VR is in the middle, is the heart of the piece, but the way that people experience is that there’s a physical space that people go in. This is what we call the freezing room or the refrigerator, which is basically a room where immigrants, where they are caught in the desert, they are put in these refrigerators where it’s freezing. They are really in a very low temperature with kids and moms and everybody. So one of the biggest decision that we took was that that was the end of the journey of the immigrants, but I decided to inverse and put the last part of the trip in the beginning, and I want the people to just physically be sensorially affected. So the people go into these white concrete, luminous room with neon white light and benches of metal. You are ordered to take out your shoes and you are barefoot and you put it in a box and you are by yourself waiting to be called by an alarm with a door, with a metal door.

And you are surrounded by a lot of shoes that has been found of people that has passed away in the desert. So all these shoes surround you in this room, the people is freezing and after four or five minutes you are called, the alarm sound, and then you go into this massive space, black, you don’t see nothing but just an orange kind of horizontal line of neon. We brought sand from the desert in Mexico. So your feet start touching the sand of the desert and then somebody help you to put your headsets. And then you get into the headsets and did a six minute, thirty-second experience where you basically will be watching the dawn in the desert and will see a group of immigrants trying to find their way. They are absolutely exhausted and you will see how they will be caught by the officers. So you leave the experience walking with them for six minutes. I think one of the particular things of this piece, I don’t know if you agree, Charlie, is that the sensorial elements of having touching the sand with your feet and when the helicopter pass– there’s a helicopter, a police helicopter, that passed that hits you with wind in your skin. That does not lie. Your mind is obviously being misled by the VR neurological elements. You think that you are there, but when the breeze hits your skin, the body doesn’t lie.

Charlie Melcher:

I was very moved by the piece, I should start by saying. So after being in that holding tank and going out now into the desert, and again, forgive me, this is my recollection and it’s from some time ago that I saw it, so it’s possible that I make some mistakes or the memory can play tricks with you. But my recollection is that I have this moment of appreciating the beauty of the desert. There’s this– I can sort of hear some of the sounds of the desert. I have a 360 view of what feels like a beautiful moment in nature. And then when the border patrol shows up and it’s the helicopter and you feel the helicopter, you see them, they’re looking for the coyote, they’re getting everyone to sit down to get down, they’re screaming. It’s very scary, honestly. It’s like, threatening and violent. And the real unbelievable moment in this is that you think that you are a little bit invisible and then all of a sudden the border patrol guard sees you, points his gun at you and screams for you to get down and you have to make that decision.

And frankly, I got down, I got down in the sand because I was afraid because I felt like I was no longer invisible and I was playing a role here in this, but it meant that I got to embody a little bit of the experience from inside of being somebody who was caught by border patrol. So yes, the multisensory parts are hugely important and it’s a new palette, right? I mean sure, anyone who makes films is used to working with visuals and audio, but you’re not used to working with temperature, wind, textures, all those things on the participants. So I am curious about how you decided to use those elements and how you sort of worked out a sensorial grammar for the piece.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

Well, there you were. You describe it much better than me. I am so happy that you described it because you did a good job by that because it’s true. The thing is, I will have to credit a lot the immigrants I work with. I think for the people to know, I interviewed 500 immigrants in LA that were struggling with their lives and with incredible stories. And finally 14, I chose that has different stories in different times and different ages. Each story of them, I wrote it with different elements and details about precise details about the journey that they have during the desert. And then I create a narrative where those 14 persons as if they would have traveled at the same time with the coyote, guided by the coyote. So all the little details that they brought to me that happened to them, I was able to really put on them for them to explore again.

So there’s kind of a journalistic kind of thing that I really collect real things and document it, and that’s what I think is very interesting. It’s not just a fictional thing, it’s performed by their own actors that lived this for true. But most importantly, it was the voice because let me tell you something. We were doing this. There was a moment, Charlie, we have been already one year in the process. A lot of money has been spent, a lot of doubts, and suddenly when we saw one of the possibilities, it looked like shit. It was really wrong. Something was wrong, something was not working. It was completely mechanic. I was so frustrated and scared because I didn’t know if we would arrive to what we wanted and it was ILM, so, the best company in the world doing this. And we were in that moment, all of us, really scared, but then I said to them, close your eyes and just hear the audio and when you hear the audio, you felt so moved. You need a little. And we said, we need to follow this audio and we need to hit that emotion with the image. And six months, eight months later, we got to a place that we said, I think we have hit something very interesting. But it was the honesty of the immigrants who really rescue the technology. What I’m saying is it was an inverse process. Now everybody: “technology is first!” No, humanity is first, and then the technology we used to get to the heart of the thing. Anyway, that was my experience.

Charlie Melcher:

Thank you. That’s a great lesson for all of storytellers, that it’s the humanity first. In fact, in my memory I thought it was live action actors. It was so well done and obviously based on live action actors, you had real actors that were caught in motion capture, real voicing and all that. So anyway, I just thought that this is one of the first virtual reality pieces where there was this combination of beautiful cinematic quality and cinematic quality animation and all of it, allowing one to suspend disbelief and really feel it.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

That’s a very great compliment. Thank you, Charlie. I think that one of the best compliments as this one that you are giving to the piece is many filmmakers, friends of mine, that went, they asked me in which format did you shoot it?

[laughter]

So many of them thought, as you, that it was cinema. I will have to say a couple of things that we did that were crucial–that were, I think, crucial for the success. First of all, the hour that we shot this was, remember, at dawn, so there was very little light. It was a balance of kind of almost moonlight. If I would have decided to make this piece at 12 o’clock in the morning, it will have been terrible because the light is horrible and then all the faces will be completely exposed and all the digital thing will be exposed. So it was a very important decision to make it in the dawn, really with low light and poetic light. Then all the wardrobe, because it’s cold in the desert: the hoods, the caps, all those things were covering skin. Another secret was the dust.

There’s a lot of dust when the helicopter comes. There’s a lot of dust particles in this air. So between the vision of the audience and the face, there’s a lot of particles. All those things, the lights of the cars and the helicopter, all that back light and all those flares make it even more dirty, more real, more– so instead to be playing this horrendous lighting and trying to make it realistic, it’s more like a dream. It’s more like a suggestion. It’s more like a sensation. I think that was my intention that the people remember–as you are telling me now, that’s why it’s a good compliment for the piece because we achieve it–is that I want the people to remember this as a dream. Not like, oh my god, what a great technological achievement. No, it’s like a memory and memories are dusty, are not clear. Like cinematic decisions help us to mitigate the limitations of the technology at that time. And I think emotionally, we succeed, I think still the piece holds very well because of those decisions that were very lucky, were very good.

Charlie Melcher:

Well, I’ve had the honor at Future of StoryTelling, of seeing a lot of virtual reality over the last 10-15 years, and I felt that so much of it made several mistakes. First, people thought that it was just about being able to show 360, and that’s really not, in my opinion, what it’s about. The early pieces were just like, “hey, look, you can look anywhere!” They didn’t realize that it was about one, creating the opportunity for people to have agency and by agency I mean the ability to move around to make decisions. But at the same time, the technology wasn’t there to be able to really bring high quality visuals and audio. So when they did do stuff, it was just not at the super high end. I mean, I am a big fan of, for example, Nonny de la Peña, who–

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

I like her a lot.

Charlie Melcher:

She did a lot of really interesting, has done a lot of really important immersive journalism, she calls it. But you look at her early works, she didn’t have big budget. She’s working with borrowed characters from other game engines and it’s very clunky. And luckily her audio also is so real. She uses real audio, but pick up animation that you kind of forgive the quality of the animation because the audio has the emotional–carries the emotional weight. But this piece is the first one where you did give real agency, where there was an emotional heart to the story, and where there was a cinematic quality level of excellence for the visuals and the interactivity and there’s actual real agency. I can wander around through the piece, I can make decisions and then I’m actually asked to make a decision at the end: Am I going to duck down when I’m screamed at gunpoint and told to get down? Or am I going to defy the border guards and stay standing and say, screw you, I’m not doing that.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

I think there’s three things to say on my side. First is that that cinematic quality, all those decisions that we made were based on the cinematic experience that Chivo and I had and what we respond to. The light and all the details that we captured during the rehearsing of the immigrants and the actors in those, the immigrants in the desert, was crucial. I always said that one of the problems of the VR, of the CGI, normally are not because the technology can or cannot do that. It’s because normally the matching lighting never match. The observation of lighting is so complex. The amount of colors that are hitting in the skin of some character, the reflections, the shadows, the movement is so complex that if it’s not observed atomically, no matter how good you are in the CGI, it always will look unreal. And I think we were obsessed that the lighting was perfectly imitated.

Secondly, I want to say that Nonny de la Peña is one of the few artists that I know that as you said… what she does has heart and has intelligence and has humanity, and that’s why her pieces are so important. She inspired me and Chivo a lot. We were in talks with her. She was super generous bringing us to her projects that she was doing, sharing with us her experience. She was very, very important in our process. I learned from her and I was inspired by her and the fact that she used this audio. And third, I want to say that as you said, I think VR is all what cinema is not. VR, it’s another medium, it’s a new medium. It’s another thing that has its own language, its own principles. I think cinema is very general. So I always said that cinema is like the ocean.

Cinema is water. It can be manifested in an ocean, it can be manifested in a cloud, it can be manifested in a cup of tea, it can be manifested in a creek, in a pond. So you have documentaries, you have docu-fiction, you have fiction. You have every genre in a way fits in what we call cinema, which is the water. VR is another animal. This is something that we cannot define yet, I think. I think we are just in the very early steps of to discover what we could do. But if we think as you said that because the people can see in 360 is what’s the point? All my life, I’m in a 360 and it’s a wonderful VR. I mean I can look, I’m now looking back and it’s fantastic, the definition, the sound. So there’s no big thing about that. I think it’s what you are telling and to choose the right theme that in a way adds to the experience to somebody that’s very important and that’s difficult.

And the other thing is that unfortunately I have to say that because it’s very expensive, most of the financiers and people are investing only to explore video games and violent things and very stimulant things. That in a way technologically can be advancing things, but I don’t think they’re doing much for the medium. I think there’s an infinite possibility of artistic, spiritual, neurological– It’s a whole universe that are not being explored because people just want to win money. But I think just to find exactly what we want to say and what we want people to think, explore or feel. There’s a universe to be explored and not only making people killing other people in video games. I think that’s the big mistake in my point of view.

Charlie Melcher:

I couldn’t agree more. And I agree with you that we’re still at the very early stages of figuring out the language, the grammar, the potential of the medium. Just like the early days of cinema, when they put a camera on a tripod and they just filmed a play, it took them 10-20 years to figure out montage and pans and cuts and that organic language of cinema we’re just beginning to do the same for VR. And the beauty of this one is that it has so much to do with both the multisensoral, right? We no longer are just playing to our eyes and our ears, but now we have all those other senses of the body. And we have–to me, the most radical difference is that we are breaking that fourth wall and we are giving agency. We’re giving that opportunity for the person formerly known as the audience to step through and now be in the story and have their choices have consequences.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

You are right, I think with an experience like this, at least in the one that I have done, which humbly is only one, but I could see that giving the people the point of view–for me, one of the most difficult questions as a director in a film is the point of view. Which point of view I want to tell this story. I’m talking about the characters, right? When you have three, four characters, which point of view I will be shooting this scene from? And depending in that point of view, the people will feel empathy or not with one character or the other. So to choose the point of view where you put the camera, it makes a huge difference in the impact of the narrative of any story. So always the people is sitting and they have to swallow the point of view that the director choose in terms of the character or the point of view of the director, where the director wanted to see the scene from.

I go to the cinema because the point of view of somebody that I love– he’s like a writer, you like how he writes, what his mind is, what is his themes? But in this case, we are giving the people the point of view in their hands, which is an amazing tool. So the people say, what is my point of view? And that’s a huge thing. One of the decisions that I made that I liked very much that some people discover and they were shocked, I don’t know if you did it, is that when you go into the bodies of somebody, you go into an audio subduction. Suddenly the audio gets like– it’s a swallowed audio, and you hear the heartbeat of a human being, like tum-tum, tum-tum, and you are in the middle of a heart and the heart is beating and you are inside a human heart with flesh.

This is something that we shoot. So this is a real flesh heart beating, and you are inside watching all the veins and all the flesh and the heart is beating, and then suddenly you go out and everybody, every–immigrants and police–has the same heart. I mean, what I would say is no matter if you are police and you are dressed of a police or you are dressed as an immigrant, we all are in the same flesh and in the same spirit and we are the same. So the people when they discover that, they were like, oh God, they didn’t know what was happening. And it’s almost like an acid dream. I think our labor, our commitment as artists is to play with the subconscious, the storage of our dreams and our memories because 95% of our decisions are made by subconscious things. We think that we are rational beings. No, we are not rational beings. We are emotional beings that sometimes rationalize. So our decisions, our lives, are made around our subconscious, so our duty is to explore the subconscious, the levels of subconscious. And I wanted to do that in this piece. It was an experiment, but I think sometimes worked for some people.

Charlie Melcher:

Let me remind you of that Marshall McCluen truism that the medium is the message. And I found myself thinking about this piece as the medium being the message. You are bringing a group of people, a group of immigrants coming across a desert, they’re lost. They’re trying to find their way. The police show up, or border guards, and they’re looking for the coyote, they’re looking for the person who’s leading them. And I started to think about this as a metaphor for the director. Normally the director is providing the path forward for the film and telling you exactly where to look or where to go and how to cross over. And here, all of a sudden we’re just wandering on our own in the desert, having to kind of create the piece and find our own path through the piece. It seems to me that somehow very fitting that this virtual reality piece that gives a lot of agency and a lot of opportunity for the participants that you would set it here in the middle of a desert where people are trying to find their way. The questions, where’s the coyote? The question could be, where’s the director? How do I make my own way through this piece? I don’t know. I just started to feel that there might a bit of a self-referential nature to it.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

I didn’t want to make this piece a political piece. I want this to be art, technology, and humanity. The combination of those three things. That’s what I believe. I think in the renaissance time, the artists were scientists, they were artists, and they were humanists. That’s how the best art normally grows. So now we separate or you are a scientist or you are an artist or you’re a politician. No, I’m interested in humans. I can use art and I can use technology… you know, it’s the meld of that kind of thing.

Charlie Melcher:

Alejandro, I love that. And it answers that question of why you did this. You didn’t mean it to be a political piece, but you can’t leave that not appreciating the desire to help create empathy with these people who had to make these very difficult and risky decisions to leave and to try to make their way to the United States. And I mean, I certainly felt a kind of connection that was stronger than if I had just sat and watched a documentary about the crisis or about their lives because I had been literally, I wasn’t walking in their shoes. I had no shoes on, but I was walking in their footsteps in a way and feeling some of the emotion that they were feeling and understanding a little bit, a little bit, very small, but a very little bit of the reality of their journey. And politicians try to dehumanize people so that they can play on fear and hate. And you are doing exactly the opposite of trying to humanize so that we can care and love and understand.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

And that’s how I discover at the end of the show, at the end of the installation, there’s a book where we allow people to write whatever they feel about the experience. And Charlie, I have never– nobody could dream ever after a film to be reviewed like that. There is no film that could ever get the people so aware, conscious, and move by this piece. I mean the things that people have write, from Obama to immigrants, to people from all around the world–what people write after the experience is so moving because it’s almost like a transformative thing and it’s because there’s real contact. And when you go through six minutes and a half of this in a real connection and you give your full attention, you are by yourself. No phone. You cannot be sending images your Instagram. That you are not there for anybody to be bragging about your experiences, it’s you with yourself. That real connection is what make us human. And we have been losing that because all the things that we are stimulated now.

Charlie Melcher:

And isn’t that part of the promise of virtual reality, of these types of immersive experiences, is that they can heighten our awareness, our focus. We can connect more quickly to that subconscious or body knowledge, things that are experienced in the body.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

Body, yes and no, Charlie, I’m very concerned about this because again, I think everything is about who is doing it and what is the theme you are talking about. Because I can say something. Two things that are for me, very, very dangerous and very scary and I’m very concerned. One is that as this piece probably can make you think about the reality of other people and put your heart more sensitive toward the other people’s reality and have more empathy–not compassion, empathy, to really understand the pain of other. But at the same time, I can use this same technology to exacerbate exactly the other thing. I can really exacerbate your hate. I can exacerbate your point of view to the matter that you think differently from something you love or that it was common sense, and suddenly I poison you by suddenly misleading you to a reality to hate, to separate yourself from something, and to start exacerbating things that will make you much more unhappy and miserable and detached from humanity and make you an angry person.

And that’s a danger. And I include the video games, which is about kids killing people. No matter who you are killing, but you have to kill something to be happy. So it’s just exacerbating the fact that I have to abort something, to reject something, to be empowered and to end the life of something. I think those video games are just like porn. Anyway, so that’s one thing. So this technology has the same capacity to do wrong. And the other thing is just I saw this announcement of Mark Zuckerberg trying to bring us in the metaverse and suddenly having these headsets where I will be seeing you instead of seeing your face in a screen. That is already–we don’t know each other physically, but you are seeing my face at least in one dimension, and we kind of know, what does that mean. But imagine that we will have now our headsets and I will be watching you in virtual reality and I will see you, your skin, and do we really think that it’s a better reality to be living with headsets and that we will be closer because I will be seeing you in 3D digital avatar and that will make me closer to you? Is that the promise? Is that all this guy can bring to the world?

Really? Is it not the saddest thing in the world, the ignorance and to even enclose and surround more people with unreality and the lack of empathy when we don’t– I prefer to see your eyes. Because at least this screen I can see your eyes, but when a machine is literally interpretating this, I’m very concerned about this. I think if that’s the future, then virtual reality can be maybe a very, very, very dangerous tool, wrongly used. I don’t know what you think about it.

Charlie Melcher:

Well, I think the same. I think that these ultimately are just tools and they can be used for good or for evil. One of the things I always like to preach at the Future of StoryTelling is that we as storytellers have unbelievably powerful tools. I mean, we wield tremendous power because we can move people to their core. We can make them believe things or disbelieve things. And when you have that kind of power or tools, you have to act with a moral compass. I think that’s the message is that we have to use those skills for good. We have to hope that there are more artists thinking about how to tell stories that are going to make the world a better place.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

No, that’s for sure. That’s for sure, always there’s tools. But again, when the masses has access to that, and suddenly we’ll be surrounded by headsets… I’m really concerned about it because all the promises that they did with social media being anonymous and speaking to anybody and saying whatever you want and exacerbating hate and opinion in everything, and the microphone is open for everybody 24 hours. That cacophony is so loud that nobody is able to communicate respectfully and disagreeing with respect and bringing ideas. It’s just shouts, insults and rage. And so what I’m saying is the danger of all these technology and the access of, without knowledge how to use it, I’m really concerned because these companies are just basically charging rent in our communication. That’s what they have just done. They are not doing nothing. Every time that I communicate with somebody, somebody is getting some dollar, right?

These people that are just charging rent for our communication, but now they want our faces and our things and we have to be very conscious about that, that it is just to give so much power and then the restrictions of to be in touch with your body. That’s the most dangerous thing, Charlie, I want to mention. One of the most important things to understand, the miserability of many people is that we are living in our heads and in our intellectual minds, and the mind is very dangerous. And if we are not in touch with our bodies…that is the principle of meditation, the body doesn’t lie. If you are not connected to your body, you don’t know where you are, and the mind is ignorant, the mind is going everywhere and there’s tons of thoughts and emotions every minute. That doesn’t mean nothing. And you are not in control of your mind.

And these technologies sometimes bring you out of your mind. I knew. I know because I know when the people put the headset, six minutes and a half, they are not there. I put them where I want them to be. So look at the power that I have on them. If I put it in the wrong place, emotionally, intellectually and physically, it’s dangerous. So what I’m saying is the more we are in our phones, in our headsets, in our things, we are detached from our body connection and we can be manipulate, and we are not us. We are basically mind-thoughts that go—energy and frequency and electromagnetic field frequencies, that’s all what we are. And so we can be sent to every place by the power of corporation. And I don’t want to be dystopian here, but it’s true. I mean, this is science. This is not an opinion. This is absolutely true. So I hope that I don’t want to be so dark, but I would say yes, there’s a great opportunity to make a Renaissance art with VR, I think it’s a beautiful medium. Again, used in the wrong, and in order to capitalize and make corporations bigger and stronger, is an incredible danger. Like, scary danger, you know?

Charlie Melcher:

Okay, so let me respond to this. So first of all, I don’t believe that virtual reality headsets are the future. I think those are going to come and go. I believe that we’re going to experience our human digital interface through more natural ways. In fact, I think we’re already evolving. Technology’s evolving to be more responsive to human beings. So just think about what sitting there typing over a keyboard or using your two thumbs and looking down into your little phone, that’s not how we evolved as a species to interact, right? This is a weird moment in the evolution of technology that we’re doing it this way. But you start to see all these natural user interfaces like voice, like gesture, being able to have sensors that pick up your physical movement. There are all sorts of new natural user interfaces that allow us to actually reconnect with our bodies and to be able to still interact with the digital age.

And so I think that the tech will become more and more invisible and it will allow us to interact in ways that we are meant to as human beings. And it’s just going to augment the ways that we are meant to interact. And I find that very hopeful because I do believe that we evolved over millennia in the forest hunting and gathering, moving our bodies. And granted, I’m aware that I’m a bit of a utopian, that’s a utopian vision. But I do think over history, technology has so far, the benefits have outweighed the negatives. I mean, look at the explosion of people writing things, singing, making videos of themselves dancing. Like just in the last 10 years, the explosion of creative expression globally enabled by that–those tools that you were saying can be used for bad– is amazing. Never in human history. I’m not saying some people will not use it for ill or for bad, but I also think that we’re training a generation of storytellers and creators. And not that all of them are going to have careers making movies or doing dances or writing or singing, but maybe they’ll appreciate those forms more because they made a few of them or they’ve played in them, or maybe it’s just going to be easier for them to express themselves in these ways. And through that, maybe we will get to some place where we can have more empathy and connection with each other.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

Nothing more I will love that you are right, Charlie. You are a very, very positive person. We need that. I am not as positive as you. I have to say, I am seeing much more damage that has been done in the last years by in communication, by the lack of communication, by the misleading information, by the fake, the fact that you can be anonymous and you can spit in the face of somebody with no being identified and said whatever you want anytime about anything and can create confusion and fear or hate. The language is such a powerful thing. William Burroughs has this incredible theory that in a way, he was right about language. It’s like a virus. The words are virus. Human beings are the only ones that, with these phonetic words, we are basically, our minds are built with these bits of phonetic words that mean something, right?

Flower is a flower, but flower is not a flower. We just call it flower. But we synthesize the value of that. And from there, every word in a way create our ideology, our beliefs. So when somebody manipulate the language and the words in a way to change the narrative, then facts and realities doesn’t matter anymore. It’s just the way you tell it. So there’s people now that are so good about changing the narrative and basically planting words in people’s mind that then people believe in what they haven’t seen, in what is not true. So even climate change when it’s happening and we are feeling in our skins, and every day there’s something, there’s still people that does not believe in it. What I’m saying is the language and the images and all this technology can easily mislead the reality and detach us from the real things and the facts.

That is what is happening. And we are living in our minds. And the minds are very easily manipulate, as you know, by all these tools and language. So the amount of language and videos of people dancing is distracting us for real communication. Not everybody has something to say. I don’t have nothing to say most of the time in my life. Why I’m going to be opinionated about anything when I don’t know actually the facts? Even my emotions, why I have to express publicly because I will affect positively or negatively– what I’m saying is the amount of possibilities now I don’t think necessarily are a great news. What I think there’s going to be a moment that we will have to analyze that sometimes that amount of tools, they have to be in a way regulated in a much more smarter way in the benefit of all human beings, not because they exist. You need to use it. That’s the thing.

Charlie Melcher:

Where are you in your next project and has your experience with Carne y Arena influenced or changed the way you make your films?

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

Carne y Arena was something that was a once in a lifetime experience that I will like to repeat again someday when I have a good idea or a good reason to explore VR. I have been trying to get some ideas that are in development just to understand if it’s really worth to again, devote myself, one year at least, to really make it happen because I really love it. And at the same time, I think that, for example, the last film that I did, Bardo… In a way, the way I shot it was again, with wide lenses and trying that the people just really being in a dream all the time. So, “bardo” is the Buddhist kind of meaning for transition from after you die, where are you going? So it’s that transition, like limbo in the Catholic meaning. So I want the experience of the film to be that, to be just something that you are living through the consciousness of somebody that is losing his life and all his memories basically, and the time and the space is being liquid and start leaving. So the film is an exploration of the liquid memory of the last time of a life of a person. So I will say in the grammar of Carne y Arena, that, but it’s just through the point of view of a person that is basically passing away, that’s what I want.

Charlie Melcher:

And have you tried even more immersive media like going to immersive theater, Punchdrunk or Third Rail, “Then She Fell”? Those kinds of, where you’re in the story and you’re interacting with actors?

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

I would love to do– I love Punch Drunk. I think they do an amazing work. I saw the last one in London. No, I love that. But I think it’s another thing. I would love to do theater, by the way. I’m planning to do theater soon, so I will love to do that because the physicality and the immediacy and the risk of it is for me will be kind of interesting. Yeah, the Punchdrunk and thing like that is huge. It’s another world, I think. I would love to, but I don’t think I have that skills. But theater, yes, I’m very interested to do theater once in my life, I hope.

Charlie Melcher:

Well, I love the fact that you are constantly looking to take on new challenges to try something you haven’t done before. I think that’s a great inspiration for everyone. I know that you could easily rest on your laurels, as they say, that expression.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

Well, first of all, I think I would like to invite every artist, like architects, sculptors sculpting people, painters, dancers, musicians. I think– I hope they really could explore VR as a possibility because nobody should be afraid of it. Once you get in, you will understand how it works. It’s just, you start just to put your feet in the water and then you will understand the principles of it. And it’s fun. So I hope that more people can get in and to be supported to get into that, and not only the video games. I hope that more artists can create spaces, emotions, universe, thoughts, frequencies through the VR, and I think that will be very important. That it’s available in some way. And the last thing that I want say is that thankfully through Emerson Collective and PHI in Canada and Legendary and Fondazione Prada, Carne y Arena is still going on. In the next year, it’ll be in another United States cities, which we will announce, and we are trying to get the next year to some European cities to be played. But we will announce the next round of opening shows again, because many people wanted to see it and couldn’t see it.

Charlie Melcher:

That’s such great news there. That’s an optimistic note to end on, and I hope that everyone who listens, who hasn’t seen it will go experience it because it’s very much worth doing. So we should mention by the way, it received an honorary Oscar in 2017, keeping up your Run there of wins. I think it’s the first virtual reality piece to ever have received that kind of acknowledgement from the Academy.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

That was an award for all of us. It was a collective effort. Carne y Arena was the first VR installation that compete officially in the Cannes Film Festival. As a piece, was the first VR in competition in Cannes. And then we were honored by this incredible honorific Oscar of technology that since Toy Story has not been given, and Toy Story is one of my favorite films ever. So I was thrilled about it because when I remember Toy Story for me is an achievement in every level, storytelling, narratively, technically, humanly, all that. So suddenly that after that we got that. I felt so happy for all the people that trust in this piece. That was a crazy idea to make because what I admire of the people that support it… Miucca Prada and Mary Parent… there was no an economic interest. We all did it by the right reason. So it came from the right side, which is the heart. And suddenly this award was very beautiful because it worked. It worked. So it was very beautiful for all of us.

Charlie Melcher:

Well, there’s the message. Follow your heart.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

It is, it is. We forgot about it. We are too much in our minds.

Charlie Melcher:

Alejandro, thank you so much for this time, for this wonderful conversation, for your generosity, for your creativity, and just as an inspiration for so many of us storytellers.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

Charlie, thank you very much for your time and for your interest. Thank you for this interview. It was a pleasure to talk to you. Thank you very much. And thank you for all the audience that listen to this. I hope they have the patience and optimism. Let’s be optimistic. We need that. It’s true. You are right. I think we have to connect the young people. There’s too much dystopian shows in TV and things, and that put our mind in the dark places. Let’s go to the high level, to the high places and go to the light. You are right. You convinced me already.

Charlie Melcher:

Hear hear. Thank you.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu:

Thank you, Charlie.

Charlie Melcher:

I’m Charlie Melcher, and this has been The Future Storytelling Podcast. With a hundred episodes under our belt, it’s an exciting time to think about the next hundred, and we welcome your input. Please feel free to write to us at podcast@fost.org with your thoughts and suggestions. Can’t wait to hear from you. This show is only one of the ways you can learn about the latest and greatest in storytelling from FoST. There’s also our free monthly newsletter, FoST in Thought, and our annual membership program, FoST Explorers Club. You can learn more about both on our website at fost.org. The Future of Storytelling podcast is produced by Melcher Media, in collaboration with our talented friends and production partners, Charts & Leisure. I hope to see you again soon for another deep dive into the world of storytelling. Until then, please be safe, stay strong, and story on.